Ch. 1

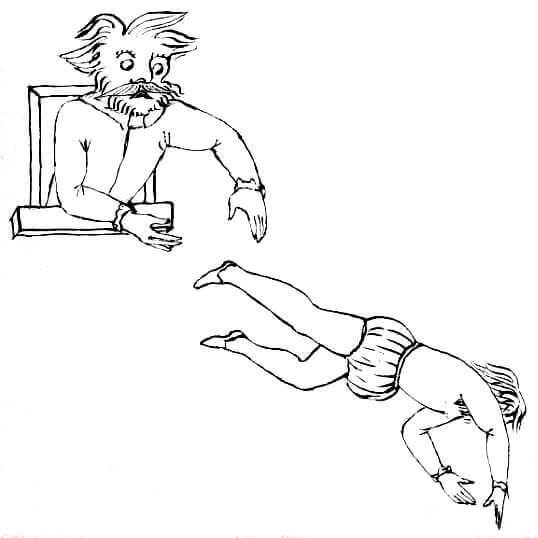

The Baron was pacing his tapestried chamber two mortal hours ere sunrise.1 Ever and anon he would pause at the open casement, and gaze from its giddy height2 on the ground beneath. Then a stern smile3 would light up his gloomy brow, and muttering to himself in smothered accents, “’twill do” he would again resume his lonely march.

Uprose the glorious sun, and illumined4 the darkened world with the light of day: still was the haughty Baron pacing his chamber, albeit his step was hastier and more impatient than before, and more than once he stood motionless, listening anxiously and eagerly, then turned with a disappointed air upon his heel, while a darker shade passed over his brow. Suddenly the trumpet5 which hung at the castle gate gave forth a shrill6 blast: the Baron heard it, and savagely beating his breast with both his clenched fists, he murmured in bitter tone “the time draws nigh, I must nerve myself for action.” Then, throwing himself into an easy chair, he hastily drank7 off the contents of a large goblet of wine which stood on the table, and in vain attempted to assume an air of indifference. The door was suddenly thrown open and in a loud voice an attendant announced “Signor Blowski!”

“Be seated! Signor! you are early this morn, and Alonzo! ho! fetch a cup of wine for the Signor! spice8 it well, boy! ha! ha! ha!” and the Baron laughed loud and boisterously, but the laugh was forced and hollow,9 and died quickly away. Meanwhile the stranger, who had not uttered a syllable, carefully divested himself of his hat and gloves,10 and seated himself opposite to the Baron, then having quietly waited till the Baron’s laughter had subsided, he commenced in a harsh grating tone, “The Baron Muggzwig greets you, and sends you this;” why did a sudden paleness overspread the Baron Slogdod’s features? why did his fingers tremble, so that he could scarcely open the letter? for one moment he glanced at it, and then raising his head, “taste the wine, Signor,” he said in strangely altered tone, “regale yourself, I pray,” handing him one of the goblets which had just been brought in.

The Signor received it with a smile, put his lips to it, and then quietly changing goblets with the Baron without his perceiving it, swallowed half the contents at a draught. At that moment Baron Slogdod looked up, watched him for a moment as he drank, and smiled the smile of a wolf.11

For full ten minutes there was a dead silence through the apartment, and then the Baron closed the letter, and raised his face: their eyes met: the Signor had many a time faced a savage tiger at bay without flinching, but now he involuntarily turned away his eyes. Then did the Baron speak in calm and measured tone: “you know, I presume, the contents of this letter?” the Signor bowed, “and you await an answer?” “I do:” “this, then, is my answer,” shouted the Baron, rushing upon him, and in another moment he had precipitated him from the open window. He gazed after him for a few seconds as he fell, and then tearing up the letter which lay on the table into innumerable pieces, he scattered them to the wind.

Ch. 2

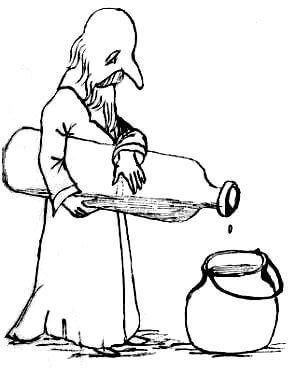

One! two! three!” The magician set down the bottle, and sank exhausted into a seat: “nine weary hours,” he sighed, as he wiped his smoking brow, “nine weary hours have I been toiling, and only got to the eight-hundred and thirty-second ingredient! a-well! I verily believe Martin Wagner12 hath ordered three drops of everything on the face of this earth in his prescription.13 However there are only a hundred and sixty-eight14 ingredients more to put in—’twill soon be done—then comes the seething15—and then—” He was checked in his soliloquy by a low timid rap outside: “’tis Blowski’s knock,” muttered the old man, as he slowly undid the bars and fastenings of the door, “I marvel what brings him here at this late hour. He is a bird16 of evil omen: I do mistrust his vulture face.17—Why! how now, Signor?” he cried, starting back in surprise as his visitor entered, “where got you that black eye? and verily your face is bruised like any rainbow!18 who has insulted you? or rather,” he muttered in an under tone, “whom have you been insulting, for that were the more likely of the two.”

“Never mind my face, good father,” hastily answered Blowski, “I only tripped up, coming home last night in the dark, that’s all, I do assure you. But I am now come on other business—I want advice—or rather I should say I want your opinion—on a difficult question—suppose a man was to—suppose two men—suppose there were two men, A and B19—” “suppose! suppose!” contemptuously muttered the magician, “and suppose these men, good father, that is A, was to bring B a letter, then we’ll suppose A read the letter, that is B, and then B tried—I mean A tried—to poison B—I mean A20—and then suppose”—“my son,” here interposed the old man, “is this a general case you are putting? Methinks you state it in a marvellously confused manner.” “Of course it’s a general case,” savagely answered Blowski, “and if you’d just listen instead of interrupting, methinks you’d understand it better!” “Proceed, my son,” mildly replied the other.

“And then suppose A—that is B—threw A out of the window—or rather,” he added in conclusion, being himself by this time a little confused, “or rather I should have said the other way.” The old man rubbed his beard,21 and mused for some time: “aye, aye,” he said at length, “I see, A—B—so so22—B poisons A—” “No! no!” cried the signor, “B tries to poison A, he didn’t really do it, I changed the—I mean,” he hastily added, turning crimson as he spoke, “you’re to suppose that he doesn’t really do it.” “Aye!” continued the magician, “it’s all clear now—B—A—to be sure—but what has all this to do with your cut23 face?” he suddenly asked. “Nothing whatever,” stammered Blowski, “I’ve told you once that I cut my face by a fall from my horse—” “ah! well! let’s see,” repeated the other in a low voice, “tripped up in the dark—fell from his horse—hm! hm!—yes, my lad, you’re in for it—I should say,” he continued in a louder voice, “it were better—but troth I know not yet what the question is.” “Why, what had B better do,” said the signor. “But who is B?” inquired the magician, “standeth B for Blowski?” “No,” was the reply, “I meant A.” “Oh!” returned he, “now I perceive—but verily I must have time to consider it, so adieu, fair24 sir,” and, opening the door he abruptly showed his visitor out: “and now,” said he to himself, “for the mixture—let me see—three drops of—yes, yes, my lad, you’re in for it.25”

Ch. 3

It had struck twelve o’clock two minutes and a quarter. The Baron’s footman26 hastily seized a large goblet,27 and gasped with terror as he filled it with hot, spiced wine. “’Tis past the hour, ’tis past,” he groaned in anguish, “and surely I shall now get the red hot poker the Baron hath so often promised me, oh! woe is me! would that I had prepared the Baron’s lunch28 before!” and, without pausing a second he grasped in one hand the steaming goblet and flew along the lofty passages with the speed of a race horse. In less time than we take to relate it he reached the Baron’s apartment, opened the door, and—remained standing on tiptoe, not daring to move one way or the other, petrified with utter astonishment. “Now then! donkey!” roared the Baron, “why stand you there staring your eyes out like a great toad29 in a fit of apoplexy?” (the Baron was remarkably choice in his similes:) “what’s the matter with you? speak out! can’t you?”

The unfortunate domestic made a desperate effort to speak, and managed at length to get out the words “Noble Sir!” “Very good! that’s a very good beginning!” said the Baron in a rather pacified tone for he liked being called “noble,” “go ahead! don’t be all day about it!” “Noble Sir!” stammered the alarmed man, “where—where—ever—is—the stranger?” “Gone!” said the Baron sternly and emphatically, pointing unconsciously his thumb over his right shoulder, “gone! he had other visits to pay, so he condescended30 to go and pay them—but where’s my wine?” he abruptly asked, and his attendant was only too glad to place the goblet in his hands, and get out of the room.

The Baron drained the goblet at a draught,31 and then walked to the window: his late victim was no longer to be seen, but the Baron, gazing on the spot where he had fallen muttered to himself with a stern32 smile, “methinks I see a dint33 in the ground.” At that moment a mysterious looking figure34 passed by, and the Baron, as he looked after him, could not help thinking “I wonder who that is!” long time he gazed after his retreating footsteps, and still the only thought which rose to his mind was “I do wonder who that is!”

Ch. 4.

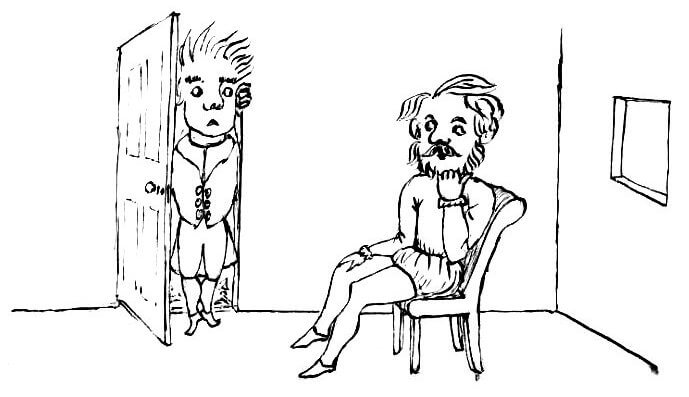

Down went the western sun, and darkness was already stealing35 over the earth when for the second36 time that day the trumpet which hung at the Baron’s gate was blown. Once more did the weary domestic ascend to his master’s apartment, but this time it was a stranger whom he ushered in, “Mr Milton Smith”! The Baron hastily rose from his seat at the unwonted37 name, and advanced to meet his visitor.

“Greetings fair, noble sir,” commenced the illustrious visitor, in a pompous tone and with a toss38 of the head, “it betided me to hear of your name and abode, and I made high resolve to visit and behold you ’ere night!” “Well, fair sir, I hope you are satisfied with the sight,” interrupted the Baron, wishing to cut short a conversation he neither understood nor liked. “It rejoiceth me,” was the reply, “nay, so much so that I could wish to prolong the pleasure, for there is a Life and Truth39 in those tones which recall to me scenes of earlier days—” “does it indeed?” said the Baron, considerably puzzled; “ay soothly,” returned the other, “and now I bethink me,” walking to the window, “it was the country likewise I did desire to look upon; ’tis fine, is’t not?” “It’s a very fine country,40” replied the Baron, adding internally, “and I wish you were well out of it!”

The stranger stood some minutes gazing out of the window, and then said, suddenly turning to the Baron, “you must know, fair sir, that I am a poet!” “Really?” replied he, “and pray what’s that?” Mr Milton Smith made no reply, but continued his observations, “perceive you, mine host, the enthusiastic41 halo which encircles yon tranquil mead?” “The quickset hedge, you mean;” remarked the Baron rather contemptuously, as he walked up to the window. “My mind,” continued his guest, “feels alway a bounding—and a longing—for—what is True and Fair42 in Nature, and—and—see you not the gorgeous rusticity—I mean sublimity, which is wafted over, and as it were intermingled with the verdure—that is, you know, the grass?” “Intermingled with the grass? oh! you mean the butter-cups43?” said the other, “yes, they’ve a very pretty effect.” “Pardon me,” replied Mr Milton Smith, “I meant not that, but—but I could almost poetise thereon!

“Lovely meadow, thou whose fragrance

“Beams beneath the azure sky,

“Where repose the lowly—” “vagrants,”44 suggested the Baron: “vagrants!” repeated the poet, staring with astonishment, “yes, vagrants, gipsies you know,” coolly replied his host, “there are very often some sleeping down in the meadow.” The inspired45 one shrugged his shoulders, and went on

“Where repose the lowly violets,” “violets doesn’t rhyme half as well as vagrants,” argued the Baron, “can’t help that,” was the reply:

“Murmuring gently”—“oh my eye!”44 said the Baron, finishing the line for him, “so there’s one stanza done, and now I must wish you good night; you’re welcome to a bed, so, when you’ve done poetising, ring the bell, and the servant will show you where to sleep.” “Thanks,” replied the poet, as the Baron left the room.

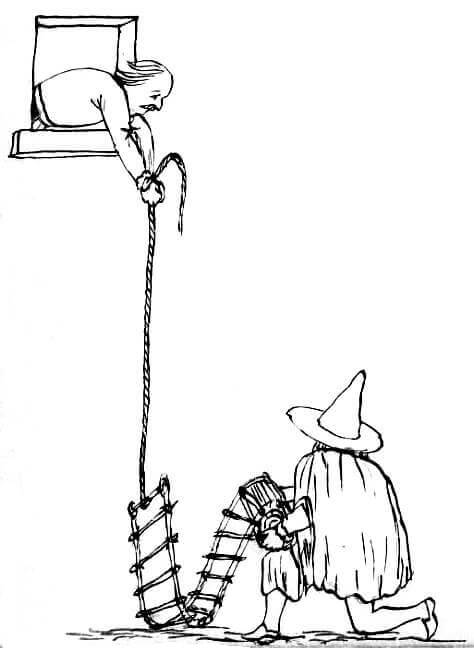

“Murmuring gently with a sigh—Ah! that’s all right,” he continued when the door was shut, and leaning out of the window he gave a low whistle. The mysterious figure in a cloak immediately emerged46 from the bushes, and said in a whisper, “all right?” “all right,” returned the poet, “I’ve sent the old covey47 to sleep with some poetry, by the bye I nearly forgot that stanza you taught me, I got into such a fix! However the coast is clear now, so look sharp.” The figure then produced a rope ladder from under his cloak, which the poet proceeded to draw up.

Ch. 5

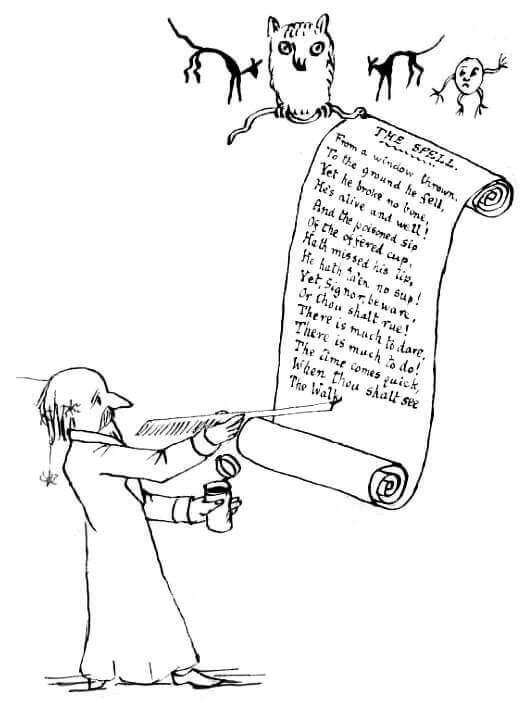

The Spell

From a window thrown,

To the ground he fell,

Yet he broke no bone,

He’s alive and well!

And the poisoned sip

Of the offered cup,

Hath missed his lip,

He hath ta’en no sup!

Yet, Signor, beware,

Or thou shalt rue!

There is much to dare,

There is much to do!

The time comes quick,

When thou shall see

The Walk…

Reader! dare you enter once more the cave of the great Magician? If your heart be not bold, abstain: close these pages: read no more. High in air suspended hung the withered forms of two black cats; between was an owl, resting on a self-supported hideous viper.

The spiders were crawling on the long grey hair of the great Astrologer, as he wrote with letters of gold an awful spell on the magic scroll which hung from the deadly viper’s mouth. A strange figure like an animated48 potatoe with arms and legs hovered over the mystic scroll, and appeared to be reading the words upside down. Hark!

A shrill scream rolled round the cave, echoing from side to side till it died49 away in the massive roof. Horror! yet did not the Magician’s heart quail, albeit his little finger shook slightly thrice, and one of his grey hairs stood out straight from his head, erect with terror: there was one other that would have followed it’s example, but a spider was hanging on it, and it could not.

A flash of mystic light, black50 as the darkest ebony, now pervades the place, and in it’s momentary gleam the owl is seen to wink once. Dread omen! Did it’s supporting viper hiss? Ah no! that would be too terrible! In the deep dead silence which followed this thrilling event, a solitary sneeze was distinctly heard from the left hand cat. Distinct, and now the Magician did tremble. “Gloomy spirits of the vasty deep!” he murmured in faltering tone, as his aged limbs seemed about to sink beneath him, “I did not call for ye: why come ye?” He spoke, and the potatoe answered, in hollow tone: “Thou didst!” then all was silence.

The magician recoiled in terror. What! bearded51 by a potatoe!52 never! He smote his aged breast in anguish, and then collecting strength to speak, he shouted, “Speak but the word again, and on the spot I’ll boil thee!” There was an ominous pause, long, vague, and mysterious. What is about to happen? The potatoe sobbed audibly, and it’s thick showering tears were heard falling heavily down on the rocky floor. Then slow, clear, and terrible came the awful words: “Gobno strodgol slok slabolgo53!” and then in a low hissing whisper “’tis time!”

“Mystery! mystery!” groaned the horrified Astrologer, “The Russian war cry! oh Slogdod! Slogdod! what hast thou done?” He stood expectant, tremulous; but no sound met his anxious ear, nothing but the ceaseless dribble of the far off waterfall. At length a voice said “now!” and at the word the right hand cat fell with a heavy thump to the earth. Then an Awful Form54 was seen, dimly looming through the darkness: it prepared to speak, but a universal cry55 of “corkscrews!” resounded through the cave, and with a noiseless howl it vanished. A rapid fluttering was now heard pervading the whole cave, three56 voices cried “yes!” at the same moment, and it was light. Dazzling light, so that the Magician shuddering closed his eyes, and said, “it is a dream, oh that I could wake!” He looked up, and cave, Form, cats, everything were gone: nothing remained before him but the magic scroll and pen, a stick of red sealing wax, and a lighted wax taper.

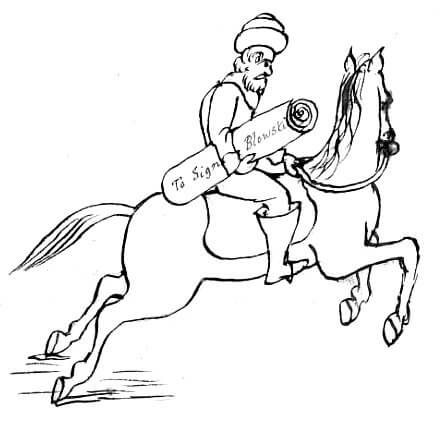

“August potatoe!” he muttered, “I obey your potent voice.” Then sealing up the mystic roll, he summoned a courier, and dispatched it: “haste for thy life, post! haste! haste! for thy life post! haste!” were the last words the frightened man heard dinned in his ears as he galloped off.

Then with a heavy sigh the great magician turned back into the gloomy cave, murmuring in a hollow tone, “now for the toad57!”

Ch. 6

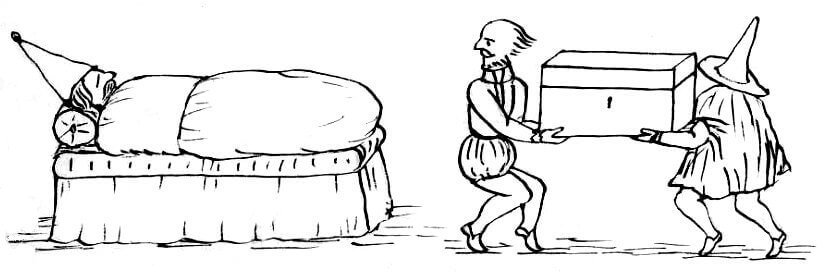

Hush! The Baron slumbers! two men with stealthy steps are removing his strong-box.58 It is very heavy, and their knees tremble, partly with the weight, partly with fear. He snores and they both start: the box rattles, not a moment is to be lost, they hasten from the room. It was very, very hard to get the box out of the window but they did it at last, though not without making noise enough to waken ten ordinary sleepers: the Baron, luckily for them, was an extraordinary sleeper.

At a safe distance from the castle they set down the box, and proceeded to force off the lid. Four mortal hours59 did Mr Milton Smith and his mysterious companion labour thereat: at sunrise it flew off with a noise louder than the explosion of fifty powder-magazines,60 which was heard for miles and miles around. The Baron sprang from his couch at the sound, and full furiously did he ring his bell: up rushed the terrified domestic, and tremblingly related when he got down stairs again, how “his Honour was wisibly flustrated, and pitched the poker61 at him more than ordinary savage-like!” But to return to our two adventurers: as soon as they recovered from the swoon into which the explosion had thrown them, they proceeded to examine the contents of the box. Mr M. Smith timidly put his head into it, his companion still remaining strechted on the ground, and being too lazy to get up.

M. Smith drew a long breath, and ejaculated, “Well! I never!” “Well! you never!” angrily repeated the other, “what’s the good of going on like that? just tell us what’s in the box, and don’t make such an ass of yourself!” “My dear fellow!” interposed the poet, “I give you my honour—” “I wouldn’t give twopence62 for your honour;” retorted his friend, savagely tearing up the grass by handfuls, “give me what’s in the box, that’s a deal more valuable.” “Well but you won’t hear me out, I was just going to tell you; there’s nothing whatever in the box but a walkingstick! and that’s a fact; if you won’t believe me, come and look yourself!” “You don’t say so!” shouted his companion, springing to his feet, his laziness gone in a moment, “surely there’s more than that!” “I tell you there isn’t!” replied the poet rather sulkily, as he stretched himself on the grass.

The other one however turned the box over, and examined it on all sides before he would be convinced, and then carelessly twirling the stick on his forefinger he began: “I suppose it’s no use taking this to Baron Muggzwig? it’ll be no sort of use.” “Well, I don’t know!” was the somewhat hesitating reply, “it might be as well—you see he didn’t say what he expected—” “I know that, you donkey!” interrupted the other impatiently, “but I don’t suppose he expected a walkingstick! if that had been all, do you think he’d have given us ten dollars a piece to do the job?” “I’m sure I can’t say,” muttered the poet: “well! do as you please then!” said his companion angrily, and flinging the walkingstick at him as he spoke he walked hastily away.

Never had he of the hat and cloak thrown away such a good opportunity of making his fortune! At twelve63 o’clock that day a visitor was announced to Baron Muggzwig, and our poet entering placed the walkingstick in his hands. The Baron’s eyes flashed with joy, and hastily placing a large purse of gold in his hand he said, “adieu for the present, my dear friend! you shall hear from me again!” and then he carefully locked up the stick muttering, “nothing is now wanting but the toad!”

Ch. 7

The Baron Muggzwig was fat.64 Far be it from the humble author of these pages to insinuate that his fatness exceeded the bounds of proportion, or the manly beauty of the human figure, but he certainly was fat, and of that fact there is not the shadow of a doubt. It may perhaps have been owing to this fatness of body that a certain thickness and obtuseness of intellect was at times perceptible in the noble Baron. In his ordinary conversation he was, to say the least of it, misty and obscure, but after dinner or when at all excited his language certainly verged on the incomprehensible. This was perhaps owing to his liberal use of the parenthesis without any definite pause to mark the different clauses of the sentence. He used to consider his arguments unanswerable, and they certainly were so perplexing, and generally reduced his hearers to such a state of bewilderment and stupefaction, that few ever ventured to attempt an answer to them.

He usually however compensated65 in length for what his speeches wanted in clearness, and it was owing to this cause that his visitors, on the morning we are speaking of had to blow the trumpet at the gate three times before they were admitted, as the footman was at that moment undergoing a lecture from his master, supposed to have reference to the yesterday’s dinner, but which, owing to a slight admixture of extraneous matter in the discourse, left on the footman’s mind a confused impression that his master had been partly scolding him for not keeping a stricter watch on the fishing trade, partly setting forth his own private views on the management of railway shares, and partly finding fault with the bad arrangement of financial affairs66 in the moon.

In this state of mind it is not surprising that his first answer to their question, “is the Baron at home?” should be, “the fish, sir, was the cook’s affair, I had nothing whatsumdever to do with it,” which on reflection he immediately afterwards corrected to, “the trains was late, so it was unpossible as the wine could come sooner.” “The man is surely mad or drunk!” angrily exclaimed one of the strangers, no other than the mysterious man in a cloak: “not so,” was the reply in gentle voice, as the great magician stepped forward, “but let me interrogate him—ho! fellow!” he continued in a louder tone, “is thy master at home?” The man gazed at him for a moment like one in a dream, and then suddenly recollecting himself he replied, “I begs pardon, gentlemen, The Baron is at home: would you please to walk in?” and with these words he ushered them up stairs.

On entering the room they made a low obeisance, and the Baron starting from his seat exclaimed with singular rapidity, “and even if you have called on behalf of Slogdod that infatuated wretch and I’m sure I’ve often told him—” “we have called,” gravely interrupted the magician, “to ascertain whether—” “yes” continued the excited67 Baron, “scores of times aye scores of times I have and you may believe me or not as you like for though—” “to ascertain,” persisted the magician, “whether you have in your possession,68 and if so—” “but yet” broke in Muggzwig, “he always would and as he used to say if—” “and if so,” shouted the man in a cloak despairing of the Magician ever getting through the sentence, “to know what you would like to be done with regard to Signor Blowski.” So saying, they retired a few steps, and waited for the Baron’s reply, and their host, without further delay delivered the following remarkable69 speech: “and though I have no wish to provoke the enmity which considering the provocations I have received and really if you reckon them up they are more than any mortal man let alone a Baron for the family temper has been known for years to be beyond nay the royal family themselves will hardly boast of considering too that he has so long a time kept which I shouldn’t have found out only that rascal Blowski said and how he could bring himself to tell all those lies I ca’n’t think for I always considered him quite honest and of course wishing if possible to prove him innocent70 and the walkingstick since it is absolutely necessary in such matters and begging your pardon I consider the toad and all that humbug but that’s between you and me and even when I had sent for it by two of my bandits71 and one of them bringing it to me yesterday for which I gave him a purse of gold and I hope he was grateful for it and though the employment of bandits is at all times and particularly in this case if you consider the but even on account of some civilities he showed me though I daresay there was something and by-the-bye perhaps that was the reason he pitched himself I mean him out of the window for—” here he paused, seeing that his visitors in despair had left the room. Now, Reader, prepare yourself for the last chapter.

Ch. 8 and last

All was silence.72 The Baron Slogdod was seated in the hall of his ancestors, in his chair of state, but his countenance wore not it’s usual expression of calm content: there was an uncomfortable restlessness about him which betokened a mind ill at ease, for why? closely packed in the hall around, so densely wedged together as to resemble one vast living ocean without a gap or hollow, were seated seven thousand human beings: all eyes were bent upon him, each breadth was held in eager expectation, and he felt, he felt in his inmost heart, though he vainly endeavoured to conceal his uneasiness under a forced and unnatural smile, that something awful was about to happen. Reader! if your nerves are not adamant, turn not this page!

Before the Baron’s seat there stood a table: what sat thereon? well knew the trembling crowds, as with blanched cheek and tottering knees they gazed upon it, and shrank from it even while they gazed: ugly, deformed, ghastly and hideous it sat, with large dull eyes, and bloated cheeks, the magic toad!

All feared and loathed it, save the Baron only, who, rousing himself at intervals from his gloomy meditations, would raise his toe, and give it a sportive73 kick, of which it took not the smallest notice. He feared it not, no, deeper terrors possessed his mind, and clouded his brow with anxious thought.

Beneath the table was crouched a quivering mass, so abject and grovelling as scarce to bear the form of humanity: none regarded, and none pitied it.

Then outspake the magician: “The man I accuse,74 if man indeed he be, is—Blowski!” At the word, the shrunken form arose, and displayed to the horrified assembly the well-known vulture face: he opened his mouth to speak, but no sound issued from his pale and trembling lips … a solemn stillness settled on all around … the magician raised the walking-stick of destiny, and in thrilling accents pronounced the fatal words: “recreant vagabond! misguided reprobate! receive thy due deserts!” … Silently he sank to the earth … all was dark for a moment, … returning light revealed to their gaze … a heap of mashed potatoe75 … a globular form faintly loomed through the darkness, and howled once audibly, then all was still. Reader, our tale is told.

- i. e. probably at about 3 o’clock in the morning. ↩

- 10 feet, vide page 28. ↩

- vide page 4. ↩

- illuminated. ↩

- the usual substitute in the days of chivalry for a front-door bell. ↩

- so as to be audible at a greater distance. ↩

- drinking wine was his constant occupation. ↩

- hot spiced wine was much drunk in those days, vide page 12. ↩

- the voice was sometimes hollow as well as the laugh, vide page 42. ↩

- vide his exit without either, next page. ↩

- with most probably an hyena’s laugh. ↩

- This celebrated individual was born in Stockholm in 1548. ↩

- probably some magic charm. ↩

↩from 1000 ingredients subtract 832 and there remain 168 more to put in. - boiling. ↩

- we have a similar expression “a jail-bird.” ↩

- this the artist has not ventured to depict. ↩

- viz: violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange, red. ↩

- by this idea he clearly showed his great mathematical turn of mind. ↩

- his confusion was caused by the consciousness that he was telling falsehoods. ↩

- an action symbolical of deep thought. ↩

- meaning, “yes, yes.” ↩

- and bruised, vide page 4. ↩

- spoken ironically. ↩

- vide page 41. ↩

- or attendant. vide page 2. ↩

- the Baron’s meals seem to have consisted of nothing but hot, spiced wine. Hence his fiery temper. ↩

- the very footman calls wine his “lunch.” We know that he breakfasted on it, see page 2. ↩

- it is doubtful whether the Baron thought him most like a donkey or a toad. ↩

- a pun which the footman could not have understood. ↩

- vide page 2. ↩

- The Baron’s smile appears to have been always stern, vide page 1. His laugh was hollow, vide page 3. ↩

- probably caused by the Signor’s “vulture face, vide page 9. ↩

- vide page 28. ↩

- expressing of it’s slow and imperceptible advance. ↩

- vide page 2. ↩

- and “unwanted” too, as we afterwards learn. ↩

- vide illustration. ↩

- Dickens’ style. ↩

- i. e. by daylight, it was now growing dark. ↩

- reason sacrificed to poetry. ↩

- vide note (39), an imitation, but superior. ↩

- a sign of bad land, and as it was the Baron’s estate, we may guess from this that he was not rich. A further proof of this may be found in page 58. ↩

- the Baron had evidently a good ear for rhyme. ↩ ↩

- quasi-inspired. ↩

- came out of. ↩

- the “o” long. ↩

- it had a “hollow” voice and probably was something akin to “fishs.” vide page 35. ↩

- after it’s death it’s ghost appeared. page 43. ↩

- it is difficult to imagine what black light can look like. It may be obtained by pouring ink over a candle in a darkroom. ↩

- vide page 10. ↩

- the potatoe’s history should be carefully remembered, as it is important. ↩

- this is quoted from Punch: it is there stated that after singing this the soldiers are never known to give or receive quarter. ↩

- the ghost of the shrill scream. vide page 41. ↩

- it rolled spirally round the cave. ↩

- the Awful Form, the potatoe, and the right-hand cat. ↩

- vide page 59. the toad was always necessary to magical rites, see Shakespeare’s “Macbeth.” ↩

- it’s contents, as afterwards appears were very small. vide page 27, note (43). ↩

- probably they began at about one o’clock. ↩

- the amount of this noise can only be guessed at, as the experiment has never been tried. ↩

- probably red hot. vide page 17. ↩

- we may therefore conclude it to have been worth about three-half-pence, “honour among thieves” is a proverbial expression, so they most likely had about three-pennyworth between them. ↩

- so that it was a 7 hours’ walk from Baron Slogdod’s to Baron Muggzwig’s. ↩

- this Laconic commencement bears some resemblance to Hood’s “My aunt Shakerly was of enormous bulk,” in his “Whims and Oddities.” It his hardly necessary to state which was the original. ↩

- the author must be understood to say that length is any compensation for clearness, though there certainly have been orators who seem to have held that opinion. ↩

- our range of information on this subject is extremely limited. There would appear to be an over-hasty precipitation in the conduct of its inhabitant, who is related to have “come down too soon.” ↩

- wherefore excited? the thoughtful reader will doubtless enquire. the only circumstance we can offer in explanation is his recent squabble with the footman. ↩

- understand “the Walking-stick of Destiny.” ↩

- It is hoped that a ready solution of any little difficulties and inconsistencies which may have occured in the course of the story will be found by the attentive reader, in this speech, no less remarkable for its rapid change of subject, than for it’s uniterrupted flow. ↩

- the reader will naturally ask in what his guilt consisted, and for an answer we can only refer him to the first chapter. ↩

- this explains who the man in the cloak was. ↩

- This chapter, it is hoped, will clear up all the mystery in the story. ↩

- sportive in fact only, but the gloomy mind of the Baron was far from entertaining any sportive thoughts at that moment. ↩

- it may well be asked “of what?” and the author regrets he cannot furnish an answer. ↩

- many have vainly asked the author, “what had he done?” He don’t know. ↩