No. 1. Pixies

The origin of this curious race of creatures is not at present known: the best description we can collect of them is this, that they are a species of fairies about two feet high,1 of small and graceful figure; they are covered with a dark reddish sort of fur; the general expression of their faces is sweetness and good humour; the former quality is probably the reason why foxes are so fond of eating them. From Coleridge we learn the following additional facts; that they have “filmy pinions,” something like dragon flies’ wings, that they “sip the furze-flower’s fragrant dew,” (that, however, could only be for breakfast, as it would dry up before dinner time), and they are wont to “flash their faery feet in gamesome prank,” or, in more common language, “to dance the polka2 like winking.”

From an old English legend3 which, as it is familiar to most of our readers, we need not here repeat, we learn that they have a strong affection for raw turnips, decidedly a more vulgar sort of food than “fragrant dew”; and from their using churns and kettles we conjecture that they are not unacquainted with tea, milk, butter &cc. They are tolerably good architects, though their houses must unavoidably have something the appearance of large dog kennels, and they go to market occasionally, though from what source they get the money4 for this purpose, has hitherto remained an unexplained mystery. This is all the information we have been able to collect on this interesting subject. In our next paper we propose to discuss the natural history of “the Lory.”

No. 2. The Lory

This creature is, we believe, a species of parrot: Southey informs us that it is a “bird of gorgeous plumery,”5 and it is our private opinion that there never existed more than one, whose history as far as practicable we will now lay before our readers.

The time and place of the Lory’s birth is uncertain: the egg from which it was hatched was most probably, to judge from the colour of the bird, one of those magnificent Easter eggs6 which our readers have doubtless often seen; the experiment of hatching an Easter egg is at any rate worth trying.

That it came into the possession of Cambeo, or Cupid, at a very early age, is evident from its extreme docility, as we find him using it, by all accounts without saddle or bridle,7 for a kind of shooting pony in Southey’s poem of “the Curse of Kehama.” We need not relate its history therein contained, as our readers may see it themselves, so we proceed at once to the conclusion. When Kehama had done for the rest of the gods, and had been thereupon scorched by the combined influence of Seeva’s angry eye, and the Amreeta drink, which must have been something like fluid curry powder, it is more than probable that in the universal smash which then occurred, Cambeo’s affairs among others were wound up. His goods and chattels were then most likely put up to auction, the Lory included, which we have reason to believe was knocked down to the Glendoveer,8 in whose possession it remained for the rest of its life.

After its death we conjecture that the Glendoveer, unwilling to lose sight of its “plumery,” had it stuffed, and some years afterwards, at the suggestion of Kailyal, presented it to the Museum at York, where it may now be seen, by the inquiring reader, admittance one shilling. Having thus stated all we know, and a good deal we don’t know, on this interesting subject, we must conclude: our next subject will probably be “Fishs.”

No. 3. Fishs

The facts we have collected about this strange race of creatures are drawn partly from observation, partly from the works of a German author, whose name has not been given to the world. We believe that they9 are only to be found in Germany: our author tells us they have “ordinarely10 angles11 at them,” by which they “can be fanged, and heaved out of the water.” The specimens which fell under our observation had not angles, as will shortly be seen, and therefore this sketch12 is founded on mere conjecture.

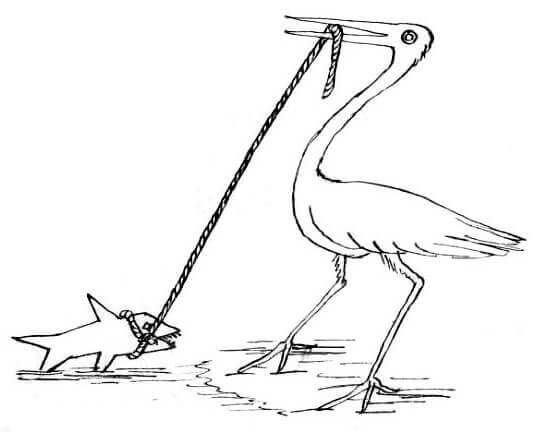

What the “fanging” consists of we cannot exactly say: if it is anything like a dog “fanging” a bone, it is certainly a strange mode of capture, but perhaps the writer refers to otters. The “heaving out of the water” we have likewise attempted to pourtray, though here again fancy is our only guide. The reader probably will aks, “why put a Crane into the picture?” our answer is “the only “heaving” we ever saw done was by means of a Crane.”

This part of the subject however will be more properly treated of in the next paper.13 Another fact our author gives us is that “they will very readily swim14 after the pleasing directions of the staff”: this is easier to understand, as the simplest reader at once perceives that the only “staff” answering to this description is a stick of barley sugar.15

We will now attempt to describe the “fishs” which we examined. Skin hard and metallic; colour brilliant, and of many hues; body hollow; (surprising as this fact may appear, it is perfectly true); eyes large and meaningless; fins fixed, and perfectly useless. They are wonderfully light, and have a sort of beak or snout of a metallic substance: as this is solid, and they have no other mouth, their hollowness is thus easily accounted for. The colour is sticky and comes off on the fingers, and they can swim back downwards just as easily as in the usual way. All these facts prove that they must not on any account be confounded with the English “fishes,” which the similarity of names might at first lead us to do. They are a peculiar race of animals,16 and must be treated as such. Our next subject17 will be “The One-winged Dove.”

No. 4: The One-Winged Dove

All the information we can collect on this subject is taken from an advertisement in the Times, July 2, 1850, the rest is conjecture.

To begin with the advertisement. “The One-winged Dove must Die, unless the Crane returns to be a shield against her enemies.” From this we draw the following facts. (1). It is a dove with one wing. (2.) The Crane is it’s friend. (3.) It has enemies who wish it’s death. (4.) The Crane alone can resist these enemies. (5.) The Crane has left it. (6.) (from the mere fact of the advertisement being sent to the Times) The Dove can write. (7.) (from the same fact) The Crane can read. (8.) (do.) The Dove has more than 12s in the world. (9.) (do.) The Crane takes in the Times.

So that here is at any rate a reasonable foundation for conjecture. You are not so clever18 as we are, Reader, so it will not be surprising if you have not yet discovered that facts (1) and (6) are connected together,19 and explain each other. Have you now? confess! There is another discovery which has probably hitherto escaped your notice, namely, that fact (2) and (3) are similarly connected.20 So now to begin.21

The Crane and the Dove are friends.22 This is natural, as they are both birds: it seems hardly necessary to speculate on the origin of this friendship, perhaps their natural talents,23 namely, reading and writing, first led to it.

The Dove has but one wing,24 that is, it has lost the other. This is unnatural, but we hope to account for it soon. It is evidently this misfortune which prevents it’s escaping from it’s enemies,25 and this gives us the first clue as to the nature of those enemies. Clearly they cannot be birds; two wings would be no protection against them: neither can they be beasts,26 against whom the Crane could be no protection27: they are as clearly not English; the Crane is not wild in England:28 insects are too contemptible a foe. There is only one thing left: come, Reader! you shall have the credit of guessing! that’s right! “Fishs.” Not “fishes,” mind! that is an English name, but “fishs.”

And we are here met by a startling, a thrilling confirmation in the fact that a Crane is to be the shield against these enemies. Turn back, Reader, to the paper29 on “Fishs”: what is employed to “fang” those “fishs”? to “heave them out of the water,” and so to destroy them? is it not a Crane? This conclusion, then, cannot be disputed.

“Fishs,” then, are the Dove’s enemies. But why? what occasioned this enemity? everything must have a reason. Be patient, Reader. The Dove, we know, is talented30: it therefore probably writes in Punch: “fishs” have “angles”: “angle” is a word of two meanings. What so natural, then, as that it should write jokes on “fishs”? This would of course enrage the said “fishs,” and enmity would thereby arise. Is not this clear enough? We know also that “fishs” were long ere this enemies to the Crane, because of it’s habit of “fanging” them, and “heaving them out of the water.” The Crane then was, of all birds, the most proper friend for the Dove to appeal to.

“But,” say you, “how could “fishs” kill the Dove?” Oh most stupid and ignorant Reader! have not “fishs” got “angles”? are not “angles” sharp and jagged? How easy then with them to kill so tender31 a creature as a One-Winged Dove! And now for the grand question, “how did the Dove lose it’s wing?” and the mysterious connection between facts (1) and (6). Reader! you shall guess again. The Dove writes in Punch32: pens are used in writing: pens are procured from feathers33: feathers from—yes! you’re right! “it uses it’s own feathers.” Perhaps you are not aware that Punch has been in existence nine years, so that if the Dove was a contributor from the first, the loss of one whole wing is thus easily accounted for. You will surely allow that thus far at least, we build our conjectures entirely on fact?

Is it likely that the Crane should have left the Dove34 in it’s present defenceless condition? Certainly not.35 We may safely conclude that it left it while still able to defend itself. When was that? Calculate for yourself, Reader. Punch comes out once a week: probably the Dove writes one article in each number,36 that is, uses one pen or feather each week: thirteen feathers would probably37 make a wing large enough to fly with: it has evidently none now: thirteen weeks from the date of it’s first advertisement brings us to April 7: can’t you guess now? Well then, we must tell you. On April 9th a great Protectionist Meeting took place in London. Still stupid? Reader! you are wonderfully slow of comprehension! does not the Crane protect the Dove? what other motive could it have then for going up to London on the 9th but attending that meeting?

And now what conclusion are we to draw from the facts that the Dove has more than 12s,38 and that the Crane takes in the Times39? We may as well just mention that 12s is the usual price40 for inserting such an advertisement in a newspaper. Simply this. The Dove is rich41: therefore it pays the Crane for defending it, and this accounts for the Crane’s taking in the Times: where else could it get the money to do so? “But where,” you ask, “where does the Dove get it’s money?” That, gentle Reader, is it’s own affair. We know that it has money because otherwise it could not advertise.

One question yet remains unanswered; “where does the Dove live?” that is easily disposed of. “Fishs” are only found in Germany. There then the Dove lives. As evidently the Crane is in England, else why advertise42 for it in an English paper? “But it left Germany thirteen weeks ago!” you say, “cruel Crane! why does it not return?” Reader, we echo the question, and we tremble as we do so.

The life of a Crane in England is no safe or easy life: even at this moment probably the Crane is either dead or in a cage. This alone can account for it’s silence. Alas! poor Dove43! what will you do? you state yourself that you “must die.” We fear it is only too true.

We are aware that one objection can be brought against this argument, namely, that no one remembers seeing any jokes in Punch about “Fishs.” This however is no real argument, as the statement at best is negative, and besides, how faithless a thing is memory! Will you, oh Reader, be certain you can remember every joke Punch has published for nine years?

We have dwelt thus long and earnestly on this subject, as knowing it’s difficulty and importance: still we hope we have established some facts, cleared up some doubts, solved some difficulties. At all events we have done our best: we cannot name any subject for our next paper, nor are we at all sure there will be another at all, so at any rate for the present, good Reader, farewell!

- so they are described by the inhabitants of Devonshire, who occasionally see them. ↩

- or any other step. ↩

- a tradition, introduced into notice by the Editor. ↩

- vide a similar difficulty, page 51. ↩

- plumage, feathers. ↩

- of these a full description may be found in the sixth number of the “Comet.” ↩

- a bridle would be useless. ↩

- a happy spirit with large blue wings like an Aerial Machine. ↩

- i. e. Fishs. ↩

- as he spells it. ↩

- or corners. ↩

- the “angles” however may be supposed to be correct. ↩

- vide page 46. ↩

- “float” would be a better word, as their fins are immoveable. ↩

- there is an objection to this solution, as “fishs” have no mouth. ↩

- an incorrect expression: “creatures” would be better. ↩

- vide page 46 ↩

- this is not meant to dispange the mental capacities of readers in general, or of any reader in particular. Who knows but that Faraday himself may read these pages? Yet, considering the transcendent intellects of the Editor, this assertion, in any given case, has every probability of being true. ↩

- vide page 49. ↩

- vide page 49. ↩

- not that we have not begun already, but here commences that close, learned, and unanswerable argument which has made this paper so deservedly celebrated. ↩

- fact (2). ↩

- or “accomplishments,” which, though common among men, are rarely found in other creaturs. ↩

- fact (1.) ↩

- fact (3.) ↩

- or quadrupeds ↩

- fact (4.) ↩

- see Buffon: “wild” does not here mean “savage,” but “undomesticated.” ↩

- page 33. ↩

- the use of this word is explained in the preceeding page: note (23). ↩

- by this is not meant that it is tenderer than other doves. ↩

- see preceding page. ↩

- generally of a goose or swan, but there is no reason why a Dove’s should not be used. ↩

- fact (5.) ↩

- if the Dove was tender-bodied, we may safely conclude that the Crane was tender-hearted, and would “heave” a sigh at the misfortunes of others. ↩

- that is every Thursday. The Umbrella comes out every rainy day. ↩

- this cannot be known for certain without making the experiment. ↩

- fact (8.) ↩

- fact (9.). ↩

- we believe the charge is five shillings a line: an advertisement lately inserted, which took up a whole page, cost three hundred pounds. ↩

- this is further seen from the fact that this advertisement was put in three or four days running. ↩

- how the Dove being abroad, could advertise in England, we confess we can not explain. ↩

- Shakespeare’s “Alas, poor Yorick!” though inferior to this passage in simplicity, is almost equal to it in poetical pathos. It seems hardly necessary to add that the idea was originated by the Editor, who would scorn to copy any author. ↩