Chapter I. Bruno’s Lessons.

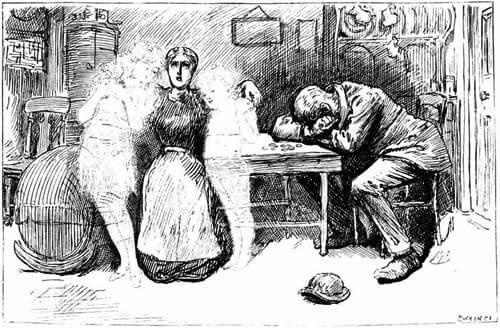

During the next month or two my solitary town-life seemed, by contrast, unusually dull and tedious. I missed the pleasant friends I had left behind at Elveston—the genial interchange of thought—the sympathy which gave to one’s ideas a new and vivid reality: but, perhaps more than all, I missed the companionship of the two Fairies—or Dream-Children, for I had not yet solved the problem as to who or what they were—whose sweet playfulness had shed a magic radiance over my life.

In office-hours—which I suppose reduce most men to the mental condition of a coffee-mill or a mangle—time sped along much as usual: it was in the pauses of life, the desolate hours when books and newspapers palled on the sated appetite, and when, thrown back upon one’s own dreary musings, one strove—all in vain—to people the vacant air with the dear faces of absent friends, that the real bitterness of solitude made itself felt.

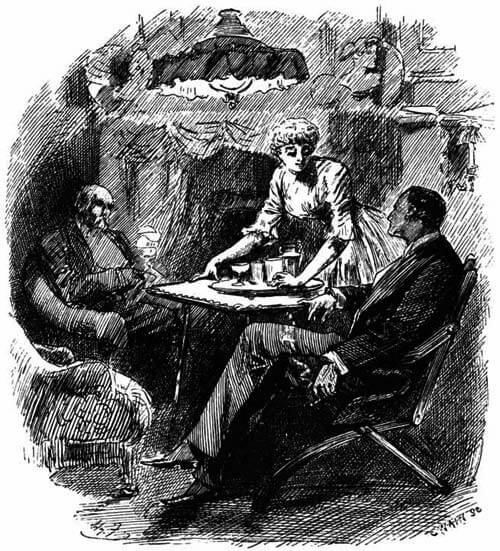

One evening, feeling my life a little more wearisome than usual, I strolled down to my Club, not so much with the hope of meeting any friend there, for London was now ‘out of town,’ as with the feeling that here, at least, I should hear ‘sweet words of human speech,’ and come into contact with human thought.

However, almost the first face I saw there was that of a friend. Eric Lindon was lounging, with rather a ‘bored’ expression of face, over a newspaper; and we fell into conversation with a mutual satisfaction which neither of us tried to conceal.

After a while I ventured to introduce what was just then the main subject of my thoughts. “And so the Doctor” (a name we had adopted by a tacit agreement, as a convenient compromise between the formality of ‘Doctor Forester’ and the intimacy—to which Eric Lindon hardly seemed entitled—of ‘Arthur’) “has gone abroad by this time, I suppose? Can you give me his present address?”

“He is still at Elveston—I believe,” was the reply. “But I have not been there since I last met you.”

I did not know which part of this intelligence to wonder at most. “And might I ask—if it isn’t taking too much of a liberty—when your wedding-bells are to—or perhaps they have rung, already?”

“No,” said Eric, in a steady voice, which betrayed scarcely a trace of emotion: “that engagement is at an end. I am still ‘Benedick the unmarried man.’”

After this, the thick-coming fancies—all radiant with new possibilities of happiness for Arthur—were far too bewildering to admit of any further conversation, and I was only too glad to avail myself of the first decent excuse, that offered itself, for retiring into silence.

The next day I wrote to Arthur, with as much of a reprimand for his long silence as I could bring myself to put into words, begging him to tell me how the world went with him.

Needs must that three or four days—possibly more—should elapse before I could receive his reply; and never had I known days drag their slow length along with a more tedious indolence.

To while away the time, I strolled, one afternoon, into Kensington Gardens, and, wandering aimlessly along any path that presented itself, I soon became aware that I had somehow strayed into one that was wholly new to me. Still, my elfish experiences seemed to have so completely faded out of my life that nothing was further from my thoughts than the idea of again meeting my fairy-friends, when I chanced to notice a small creature, moving among the grass that fringed the path, that did not seem to be an insect, or a frog, or any other living thing that I could think of. Cautiously kneeling down, and making an ex tempore cage of my two hands, I imprisoned the little wanderer, and felt a sudden thrill of surprise and delight on discovering that my prisoner was no other than Bruno himself!

Bruno took the matter very coolly, and, when I had replaced him on the ground, where he would be within easy conversational distance, he began talking, just as if it were only a few minutes since last we had met.

“Doos oo know what the Rule is,” he enquired, “when oo catches a Fairy, withouten its having tolded oo where it was?” (Bruno’s notions of English Grammar had certainly not improved since our last meeting.)

“No,” I said. “I didn’t know there was any Rule about it.”

“I think oo’ve got a right to eat me,” said the little fellow, looking up into my face with a winning smile. “But I’m not pruffickly sure. Oo’d better not do it wizout asking.”

It did indeed seem reasonable not to take so irrevocable a step as that, without due enquiry. “I’ll certainly ask about it, first,” I said. “Besides, I don’t know yet whether you would be worth eating!”

“I guess I’m deliciously good to eat,” Bruno remarked in a satisfied tone, as if it were something to be rather proud of.

“And what are you doing here, Bruno?”

“That’s not my name!” said my cunning little friend. “Don’t oo know my name’s ‘Oh Bruno!’? That’s what Sylvie always calls me, when I says mine lessons.”

“Well then, what are you doing here, oh Bruno?”

“Doing mine lessons, a-course!” With that roguish twinkle in his eye, that always came when he knew he was talking nonsense.

“Oh, that’s the way you do your lessons, is it? And do you remember them well?”

“Always can ’member mine lessons,” said Bruno. “It’s Sylvie’s lessons that’s so dreffully hard to ’member!” He frowned, as if in agonies of thought, and tapped his forehead with his knuckles. “I ca’n’t think enough to understand them!” he said despairingly. “It wants double thinking, I believe!”

“But where’s Sylvie gone?”

“That’s just what I want to know!” said Bruno disconsolately. “What ever’s the good of setting me lessons, when she isn’t here to ’splain the hard bits?”

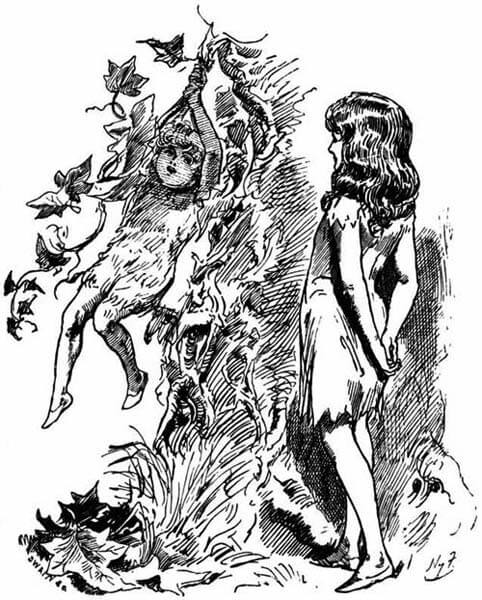

“I’ll find her for you!” I volunteered; and, getting up, I wandered round the tree under whose shade I had been reclining, looking on all sides for Sylvie. In another minute I again noticed some strange thing moving among the grass, and, kneeling down, was immediately confronted with Sylvie’s innocent face, lighted up with a joyful surprise at seeing me, and was accosted, in the sweet voice I knew so well, with what seemed to be the end of a sentence whose beginning I had failed to catch.

“—and I think he ought to have finished them by this time. So I’m going back to him. Will you come too? It’s only just round at the other side of this tree.”

It was but a few steps for me; but it was a great many for Sylvie; and I had to be very careful to walk slowly, in order not to leave the little creature so far behind as to lose sight of her.

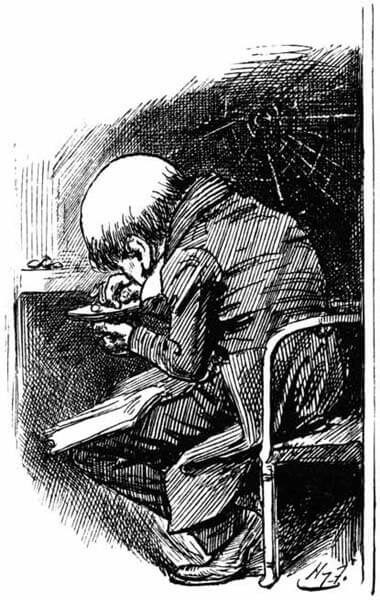

To find Bruno’s lessons was easy enough: they appeared to be neatly written out on large smooth ivy-leaves, which were scattered in some confusion over a little patch of ground where the grass had been worn away; but the pale student, who ought by rights to have been bending over them, was nowhere to be seen: we looked in all directions, for some time, in vain; but at last Sylvie’s sharp eyes detected him, swinging on a tendril of ivy, and Sylvie’s stern voice commanded his instant return to terra firma and to the business of Life.

“Pleasure first and business afterwards” seemed to be the motto of these tiny folk, so many hugs and kisses had to be interchanged before anything else could be done.

“Now, Bruno,” Sylvie said reproachfully, “didn’t I tell you you were to go on with your lessons, unless you heard to the contrary?”

“But I did heard to the contrary!” Bruno insisted, with a mischievous twinkle in his eye.

“What did you hear, you wicked boy?”

“It were a sort of noise in the air,” said Bruno: “a sort of a scrambling noise. Didn’t oo hear it, Mister Sir?”

“Well, anyhow, you needn’t go to sleep over them, you lazy-lazy!” For Bruno had curled himself up, on the largest ‘lesson,’ and was arranging another as a pillow.

“I wasn’t asleep!” said Bruno, in a deeply-injured tone. “When I shuts mine eyes, it’s to show that I’m awake!”

“Well, how much have you learned, then?”

“I’ve learned a little tiny bit,” said Bruno, modestly, being evidently afraid of overstating his achievement. “Ca’n’t learn no more!”

“Oh Bruno! You know you can, if you like.”

“Course I can, if I like,” the pale student replied; “but I ca’n’t if I don’t like!”

Sylvie had a way—which I could not too highly admire—of evading Bruno’s logical perplexities by suddenly striking into a new line of thought; and this masterly stratagem she now adopted.

“Well, I must say one thing——”

“Did oo know, Mister Sir,” Bruno thoughtfully remarked, “that Sylvie ca’n’t count? Whenever she says ‘I must say one thing,’ I know quite well she’ll say two things! And she always doos.”

“Two heads are better than one, Bruno,” I said, but with no very distinct idea as to what I meant by it.

“I shouldn’t mind having two heads,” Bruno said softly to himself: “one head to eat mine dinner, and one head to argue wiz Sylvie—doos oo think oo’d look prettier if oo’d got two heads, Mister Sir?”

The case did not, I assured him, admit of a doubt.

“The reason why Sylvie’s so cross——” Bruno went on very seriously, almost sadly.

Sylvie’s eyes grew large and round with surprise at this new line of enquiry—her rosy face being perfectly radiant with good humour. But she said nothing.

“Wouldn’t it be better to tell me after the lessons are over?” I suggested.

“Very well,” Bruno said with a resigned air: “only she wo’n’t be cross then.”

“There’s only three lessons to do,” said Sylvie. “Spelling, and Geography, and Singing.”

“Not Arithmetic?” I said.

“No, he hasn’t a head for Arithmetic——”

“Course I haven’t!” said Bruno. “Mine head’s for hair. I haven’t got a lot of heads!”

“—and he ca’n’t learn his Multiplication-table——”

“I like History ever so much better,” Bruno remarked. “Oo has to repeat that Muddlecome table——”

“Well, and you have to repeat——”

“No, oo hasn’t!” Bruno interrupted. “History repeats itself. The Professor said so!”

Sylvie was arranging some letters on a board——E—V—I—L. “Now, Bruno,” she said, “what does that spell?”

Bruno looked at it, in solemn silence, for a minute. “I knows what it doosn’t spell!” he said at last.

“That’s no good,” said Sylvie. “What does it spell?”

Bruno took another look at the mysterious letters. “Why, it’s ‘LIVE,’ backwards!” he exclaimed. (I thought it was, indeed.)

“How did you manage to see that?” said Sylvie.

“I just twiddled my eyes,” said Bruno, “and then I saw it directly. Now may I sing the King-fisher Song?”

“Geography next,” said Sylvie. “Don’t you know the Rules?”

“I thinks there oughtn’t to be such a lot of Rules, Sylvie! I thinks——”

“Yes, there ought to be such a lot of Rules, you wicked, wicked boy! And how dare you think at all about it? And shut up that mouth directly!”

So, as ‘that mouth’ didn’t seem inclined to shut up of itself, Sylvie shut it for him—with both hands—and sealed it with a kiss, just as you would fasten up a letter.

“Now that Bruno is fastened up from talking,” she went on, turning to me, “I’ll show you the Map he does his lessons on.”

And there it was, a large Map of the World, spread out on the ground. It was so large that Bruno had to crawl about on it, to point out the places named in the ‘King-fisher Lesson.’

“When a King-fisher sees a Lady-bird flying away, he says ‘Ceylon, if you Candia!’ And when he catches it, he says ‘Come to Media! And if you’re Hungary or thirsty, I’ll give you some Nubia!’ When he takes it in his claws, he says ‘Europe!’ When he puts it into his beak, he says ‘India!’ When he’s swallowed it, he says ‘Eton!’ That’s all.”

“That’s quite perfect,” said Sylvie. “Now you may sing the King-fisher Song.”

“Will oo sing the chorus?” Bruno said to me.

I was just beginning to say “I’m afraid I don’t know the words,” when Sylvie silently turned the map over, and I found the words were all written on the back. In one respect it was a very peculiar song: the chorus to each verse came in the middle, instead of at the end of it. However, the tune was so easy that I soon picked it up, and managed the chorus as well, perhaps, as it is possible for one person to manage such a thing. It was in vain that I signed to Sylvie to help me: she only smiled sweetly and shook her head.

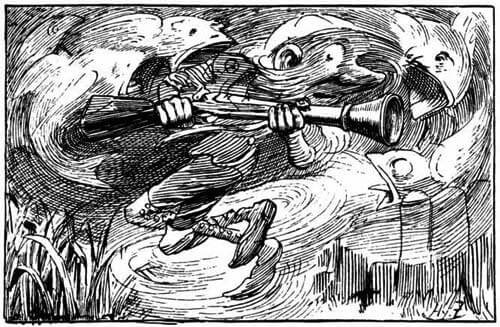

“King Fisher courted Lady Bird—

Sing Beans, sing Bones, sing Butterflies!

‘Find me my match,’ he said,

‘With such a noble head—

With such a beard, as white as curd—

With such expressive eyes!’

“‘Yet pins have heads,’ said Lady Bird—

Sing Prunes, sing Prawns, sing Primrose-Hill!

‘And, where you stick them in,

They stay, and thus a pin

Is very much to be preferred

To one that’s never still!’

“‘Oysters have beards,’ said Lady Bird—

Sing Flies, sing Frogs, sing Fiddle-strings!

‘I love them, for I know

They never chatter so:

They would not say one single word—

Not if you crowned them Kings!’

“‘Needles have eyes,’ said Lady Bird—

Sing Cats, sing Corks, sing Cowslip-tea!

‘And they are sharp—just what

Your Majesty is not:

So get you gone—’tis too absurd

To come a-courting me!’”

“So he went away,” Bruno added as a kind of postscript, when the last note of the song had died away. “Just like he always did.”

“Oh, my dear Bruno!” Sylvie exclaimed, with her hands over her ears. “You shouldn’t say ‘like’: you should say ‘what.’”

To which Bruno replied, doggedly, “I only says ‘what!’ when oo doosn’t speak loud, so as I can hear oo.”

“Where did he go to?” I asked, hoping to prevent an argument.

“He went more far than he’d never been before,” said Bruno.

“You should never say ‘more far,’” Sylvie corrected him: “you should say ‘farther.’”

“Then oo shouldn’t say ‘more broth,’ when we’re at dinner,” Bruno retorted: “oo should say ‘brother’!”

This time Sylvie evaded an argument by turning away, and beginning to roll up the Map. “Lessons are over!” she proclaimed in her sweetest tones.

“And has there been no crying over them?” I enquired. “Little boys always cry over their lessons, don’t they?”

“I never cries after twelve o’clock,” said Bruno: “’cause then it’s getting so near to dinner-time.”

“Sometimes, in the morning,” Sylvie said in a low voice; “when it’s Geography-day, and when he’s been disobe——”

“What a fellow you are to talk, Sylvie!” Bruno hastily interposed. “Doos oo think the world was made for oo to talk in?”

“Why, where would you have me talk, then?” Sylvie said, evidently quite ready for an argument.

But Bruno answered resolutely. “I’m not going to argue about it, ’cause it’s getting late, and there wo’n’t be time—but oo’s as ’ong as ever oo can be!” And he rubbed the back of his hand across his eyes, in which tears were beginning to glitter.

Sylvie’s eyes filled with tears in a moment. “I didn’t mean it, Bruno, darling!” she whispered; and the rest of the argument was lost ‘amid the tangles of Neæra’s hair,’ while the two disputants hugged and kissed each other.

But this new form of argument was brought to a sudden end by a flash of lightning, which was closely followed by a peal of thunder, and by a torrent of rain-drops, which came hissing and spitting, almost like live creatures, through the leaves of the tree that sheltered us.

“Why, it’s raining cats and dogs!” I said.

“And all the dogs has come down first,” said Bruno: “there’s nothing but cats coming down now!”

In another minute the pattering ceased, as suddenly as it had begun. I stepped out from under the tree, and found that the storm was over; but I looked in vain, on my return, for my tiny companions. They had vanished with the storm, and there was nothing for it but to make the best of my way home.

On the table lay, awaiting my return, an envelope of that peculiar yellow tint which always announces a telegram, and which must be, in the memories of so many of us, inseparably linked with some great and sudden sorrow—something that has cast a shadow, never in this world to be wholly lifted off, on the brightness of Life. No doubt it has also heralded—for many of us—some sudden news of joy; but this, I think, is less common: human life seems, on the whole, to contain more of sorrow than of joy. And yet the world goes on. Who knows why?

This time, however, there was no shock of sorrow to be faced: in fact, the few words it contained (“Could not bring myself to write. Come soon. Always welcome. A letter follows this. Arthur.”) seemed so like Arthur himself speaking, that it gave me quite a thrill of pleasure, and I at once began the preparations needed for the journey.

Chapter II. Love’s Curfew.

“Fayfield Junction! Change for Elveston!”

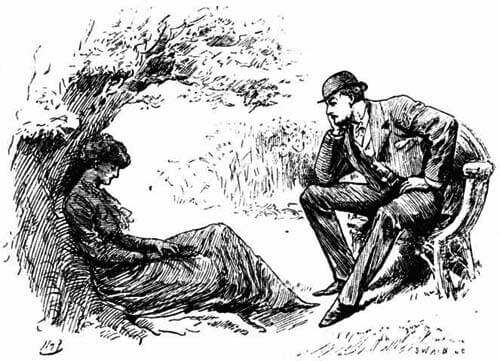

What subtle memory could there be, linked to these commonplace words, that caused such a flood of happy thoughts to fill my brain? I dismounted from the carriage in a state of joyful excitement for which I could not at first account. True, I had taken this very journey, and at the same hour of the day, six months ago; but many things had happened since then, and an old man’s memory has but a slender hold on recent events: I sought ‘the missing link’ in vain. Suddenly I caught sight of a bench—the only one provided on the cheerless platform—with a lady seated on it, and the whole forgotten scene flashed upon me as vividly as if it were happening over again.

“Yes,” I thought. “This bare platform is, for me, rich with the memory of a dear friend! She was sitting on that very bench, and invited me to share it, with some quotation from Shakespeare—I forget what. I’ll try the Earl’s plan for the Dramatisation of Life, and fancy that figure to be Lady Muriel; and I won’t undeceive myself too soon!”

So I strolled along the platform, resolutely ‘making-believe’ (as children say) that the casual passenger, seated on that bench, was the Lady Muriel I remembered so well. She was facing away from me, which aided the elaborate cheatery I was practising on myself: but, though I was careful, in passing the spot, to look the other way, in order to prolong the pleasant illusion, it was inevitable that, when I turned to walk back again, I should see who it was. It was Lady Muriel herself!

The whole scene now returned vividly to my memory; and, to make this repetition of it stranger still, there was the same old man, whom I remembered seeing so roughly ordered off, by the Station-Master, to make room for his titled passenger. The same, but ‘with a difference’: no longer tottering feebly along the platform, but actually seated at Lady Muriel’s side, and in conversation with her! “Yes, put it in your purse,” she was saying, “and remember you’re to spend it all for Minnie. And mind you bring her something nice, that’ll do her real good! And give her my love!” So intent was she on saying these words, that, although the sound of my footstep had made her lift her head and look at me, she did not at first recognise me.

I raised my hat as I approached, and then there flashed across her face a genuine look of joy, which so exactly recalled the sweet face of Sylvie, when last we met in Kensington Gardens, that I felt quite bewildered.

Rather than disturb the poor old man at her side, she rose from her seat, and joined me in my walk up and down the platform, and for a minute or two our conversation was as utterly trivial and commonplace as if we were merely two casual guests in a London drawing-room. Each of us seemed to shrink, just at first, from touching on the deeper interests which linked our lives together.

The Elveston train had drawn up at the platform, while we talked; and, in obedience to the Station-Master’s obsequious hint of “This way, my Lady! Time’s up!”, we were making the best of our way towards the end which contained the sole first-class carriage, and were just passing the now-empty bench, when Lady Muriel noticed, lying on it, the purse in which her gift had just been so carefully bestowed, the owner of which, all unconscious of his loss, was being helped into a carriage at the other end of the train. She pounced on it instantly. “Poor old man!” she cried. “He mustn’t go off, and think he’s lost it!”

“Let me run with it! I can go quicker than you!” I said. But she was already half-way down the platform, flying (‘running’ is much too mundane a word for such fairy-like motion) at a pace that left all possible efforts of mine hopelessly in the rear.

She was back again before I had well completed my audacious boast of speed in running, and was saying, quite demurely, as we entered our carriage, “and you really think you could have done it quicker?”

“No indeed!” I replied. “I plead ‘Guilty’ of gross exaggeration, and throw myself on the mercy of the Court!”

“The Court will overlook it—for this once!” Then her manner suddenly changed from playfulness to an anxious gravity.

“You are not looking your best!” she said with an anxious glance. “In fact, I think you look more of an invalid than when you left us. I very much doubt if London agrees with you?”

“It may be the London air,” I said, “or it may be the hard work—or my rather lonely life: anyhow, I’ve not been feeling very well, lately. But Elveston will soon set me up again. Arthur’s prescription—he’s my doctor, you know, and I heard from him this morning—is ‘plenty of ozone, and new milk, and pleasant society’!”

“Pleasant society?” said Lady Muriel, with a pretty make-believe of considering the question. “Well, really I don’t know where we can find that for you! We have so few neighbours. But new milk we can manage. Do get it of my old friend Mrs. Hunter, up there, on the hill-side. You may rely upon the quality. And her little Bessie comes to school every day, and passes your lodgings. So it would be very easy to send it.”

“I’ll follow your advice, with pleasure,” I said; “and I’ll go and arrange about it tomorrow. I know Arthur will want a walk.”

“You’ll find it quite an easy walk—under three miles, I think.”

“Well, now that we’ve settled that point, let me retort your own remark upon yourself. I don’t think you’re looking quite your best!”

“I daresay not,” she replied in a low voice; and a sudden shadow seemed to overspread her face. “I’ve had some troubles lately. It’s a matter about which I’ve been long wishing to consult you, but I couldn’t easily write about it. I’m so glad to have this opportunity!”

“Do you think,” she began again, after a minute’s silence, and with a visible embarrassment of manner most unusual in her, “that a promise, deliberately and solemnly given, is always binding—except, of course, where its fulfilment would involve some actual sin?”

“I ca’n’t think of any other exception at this moment,” I said. “That branch of casuistry is usually, I believe, treated as a question of truth and untruth——”

“Surely that is the principle?” she eagerly interrupted. “I always thought the Bible-teaching about it consisted of such texts as ‘lie not one to another’?”

“I have thought about that point,” I replied; “and it seems to me that the essence of lying is the intention of deceiving. If you give a promise, fully intending to fulfil it, you are certainly acting truthfully then; and, if you afterwards break it, that does not involve any deception. I cannot call it untruthful.”

Another pause of silence ensued. Lady Muriel’s face was hard to read: she looked pleased, I thought, but also puzzled; and I felt curious to know whether her question had, as I began to suspect, some bearing on the breaking off of her engagement with Captain (now Major) Lindon.

“You have relieved me from a great fear,” she said; “but the thing is of course wrong, somehow. What texts would you quote, to prove it wrong?”

“Any that enforce the payment of debts. If A promises something to B, B has a claim upon A. And A’s sin, if he breaks his promise, seems to me more analogous to stealing than to lying.”

“It’s a new way of looking at it—to me,” she said; “but it seems a true way, also. However, I won’t deal in generalities, with an old friend like you! For we are old friends, somehow. Do you know, I think we began as old friends?” she said with a playfulness of tone that ill accorded with the tears that glistened in her eyes.

“Thank you very much for saying so,” I replied. “I like to think of you as an old friend,” (“—though you don’t look it!” would have been the almost necessary sequence, with any other lady; but she and I seemed to have long passed out of the time when compliments, or any such trivialities, were possible.)

Here the train paused at a station, where two or three passengers entered the carriage; so no more was said till we had reached our journey’s end.

On our arrival at Elveston, she readily adopted my suggestion that we should walk up together; so, as soon as our luggage had been duly taken charge of—hers by the servant who met her at the station, and mine by one of the porters—we set out together along the familiar lanes, now linked in my memory with so many delightful associations. Lady Muriel at once recommenced the conversation at the point where it had been interrupted.

“You knew of my engagement to my cousin Eric. Did you also hear——”

“Yes,” I interrupted, anxious to spare her the pain of giving any details. “I heard it had all come to an end.”

“I would like to tell you how it happened,” she said; “as that is the very point I want your advice about. I had long realised that we were not in sympathy in religious belief. His ideas of Christianity are very shadowy; and even as to the existence of a God he lives in a sort of dreamland. But it has not affected his life! I feel sure, now, that the most absolute Atheist may be leading, though walking blindfold, a pure and noble life. And if you knew half the good deeds——” she broke off suddenly, and turned away her head.

“I entirely agree with you,” I said. “And have we not our Saviour’s own promise that such a life shall surely lead to the light?”

“Yes, I know it,” she said in a broken voice, still keeping her head turned away. “And so I told him. He said he would believe, for my sake, if he could. And he wished, for my sake, he could see things as I did. But that is all wrong!” she went on passionately. “God cannot approve such low motives as that! Still it was not I that broke it off. I knew he loved me; and I had promised; and——”

“Then it was he that broke it off?”

“He released me unconditionally.” She faced me again now, having quite recovered her usual calmness of manner.

“Then what difficulty remains?”

“It is this, that I don’t believe he did it of his own free will. Now, supposing he did it against his will, merely to satisfy my scruples, would not his claim on me remain just as strong as ever? And would not my promise be as binding as ever? My father says ‘no’; but I ca’n’t help fearing he is biased by his love for me. And I’ve asked no one else. I have many friends—friends for the bright sunny weather; not friends for the clouds and storms of life; not old friends like you!”

“Let me think a little,” I said: and for some minutes we walked on in silence, while, pained to the heart at seeing the bitter trial that had come upon this pure and gentle soul, I strove in vain to see my way through the tangled skein of conflicting motives.

“If she loves him truly,” (I seemed at last to grasp the clue to the problem) “is not that, for her, the voice of God? May she not hope that she is sent to him, even as Ananias was sent to Saul in his blindness, that he may receive his sight?” Once more I seemed to hear Arthur whispering “What knowest thou, O wife, whether thou shalt save thy husband?” and I broke the silence with the words “If you still love him truly——”

“I do not!” she hastily interrupted. “At least—not in that way. I believe I loved him when I promised; but I was very young: it is hard to know. But, whatever the feeling was, it is dead now. The motive on his side is Love: on mine it is—Duty!”

Again there was a long silence. The whole skein of thought was tangled worse than ever. This time she broke the silence. “Don’t misunderstand me!” she said. “When I said my heart was not his, I did not mean it was any one else’s! At present I feel bound to him; and, till I know I am absolutely free, in the sight of God, to love any other than him, I’ll never even think of any one else—in that way, I mean. I would die sooner!” I had never imagined my gentle friend capable of such passionate utterances.

I ventured on no further remark until we had nearly arrived at the Hall-gate; but, the longer I reflected, the clearer it became to me that no call of Duty demanded the sacrifice—possibly of the happiness of a life—which she seemed ready to make. I tried to make this clear to her also, adding some warnings on the dangers that surely awaited a union in which mutual love was wanting. “The only argument for it, worth considering,” I said in conclusion, “seems to be his supposed reluctance in releasing you from your promise. I have tried to give to that argument its full weight, and my conclusion is that it does not affect the rights of the case, or invalidate the release he has given you. My belief is that you are entirely free to act as now seems right.”

“I am very grateful to you,” she said earnestly. “Believe it, please! I ca’n’t put it into proper words!” and the subject was dropped by mutual consent: and I only learned, long afterwards, that our discussion had really served to dispel the doubts that had harassed her so long.

We parted at the Hall-gate, and I found Arthur eagerly awaiting my arrival; and, before we parted for the night, I had heard the whole story—how he had put off his journey from day to day, feeling that he could not go away from the place till his fate had been irrevocably settled by the wedding taking place: how the preparations for the wedding, and the excitement in the neighbourhood, had suddenly come to an end, and he had learned (from Major Lindon, who called to wish him good-bye) that the engagement had been broken off by mutual consent: how he had instantly abandoned all his plans for going abroad, and had decided to stay on at Elveston, for a year or two at any rate, till his newly-awakened hopes should prove true or false; and how, since that memorable day, he had avoided all meetings with Lady Muriel, fearing to betray his feelings before he had had any sufficient evidence as to how she regarded him. “But it is nearly six weeks since all that happened,” he said in conclusion, “and we can meet in the ordinary way, now, with no need for any painful allusions. I would have written to tell you all this: only I kept hoping from day to day, that—that there would be more to tell!”

“And how should there be more, you foolish fellow,” I fondly urged, “if you never even go near her? Do you expect the offer to come from her?”

Arthur was betrayed into a smile. “No,” he said, “I hardly expect that. But I’m a desperate coward. There’s no doubt about it!”

“And what reasons have you heard of for breaking off the engagement?”

“A good many,” Arthur replied, and proceeded to count them on his fingers. “First, it was found that she was dying of—something; so he broke it off. Then it was found that he was dying of—some other thing; so she broke it off. Then the Major turned out to be a confirmed gamester; so the Earl broke it off. Then the Earl insulted him; so the Major broke it off. It got a good deal broken off, all things considered!”

“You have all this on the very best authority, of course?”

“Oh, certainly! And communicated in the strictest confidence! Whatever defects Elveston society suffers from, want of information isn’t one of them!”

“Nor reticence, either, it seems. But, seriously, do you know the real reason?”

“No, I’m quite in the dark.”

I did not feel that I had any right to enlighten him; so I changed the subject, to the less engrossing one of “new milk,” and we agreed that I should walk over, next day, to Hunter’s farm, Arthur undertaking to set me part of the way, after which he had to return to keep a business-engagement.

Chapter III. Streaks of Dawn.

Next day proved warm and sunny, and we started early, to enjoy the luxury of a good long chat before he would be obliged to leave me.

“This neighbourhood has more than its due proportion of the very poor,” I remarked, as we passed a group of hovels, too dilapidated to deserve the name of “cottages.”

“But the few rich,” Arthur replied, “give more than their due proportion of help in charity. So the balance is kept.”

“I suppose the Earl does a good deal?”

“He gives liberally; but he has not the health or strength to do more. Lady Muriel does more in the way of school-teaching and cottage-visiting than she would like me to reveal.”

“Then she, at least, is not one of the ‘idle mouths’ one so often meets with among the upper classes. I have sometimes thought they would have a hard time of it, if suddenly called on to give their raison d’être, and to show cause why they should be allowed to live any longer!”

“The whole subject,” said Arthur, “of what we may call ‘idle mouths’ (I mean persons who absorb some of the material wealth of a community—in the form of food, clothes, and so on—without contributing its equivalent in the form of productive labour) is a complicated one, no doubt. I’ve tried to think it out. And it seemed to me that the simplest form of the problem, to start with, is a community without money, who buy and sell by barter only; and it makes it yet simpler to suppose the food and other things to be capable of keeping for many years without spoiling.”

“Yours is an excellent plan,” I said. “What is your solution of the problem?”

“The commonest type of ‘idle mouths,’” said Arthur, “is no doubt due to money being left by parents to their own children. So I imagined a man—either exceptionally clever, or exceptionally strong and industrious—who had contributed so much valuable labour to the needs of the community that its equivalent, in clothes, &c., was (say) five times as much as he needed for himself. We cannot deny his absolute right to give the superfluous wealth as he chooses. So, if he leaves four children behind him (say two sons and two daughters), with enough of all the necessaries of life to last them a life-time, I cannot see that the community is in any way wronged if they choose to do nothing in life but to ‘eat, drink, and be merry.’ Most certainly, the community could not fairly say, in reference to them, ‘if a man will not work, neither let him eat.’ Their reply would be crushing. ‘The labour has already been done, which is a fair equivalent for the food we are eating; and you have had the benefit of it. On what principle of justice can you demand two quotas of work for one quota of food?’”

“Yet surely,” I said, “there is something wrong somewhere, if these four people are well able to do useful work, and if that work is actually needed by the community, and they elect to sit idle?”

“I think there is,” said Arthur: “but it seems to me to arise from a Law of God—that every one shall do as much as he can to help others—and not from any rights, on the part of the community, to exact labour as an equivalent for food that has already been fairly earned.”

“I suppose the second form of the problem is where the ‘idle mouths’ possess money instead of material wealth?”

“Yes,” replied Arthur: “and I think the simplest case is that of paper-money. Gold is itself a form of material wealth; but a bank-note is merely a promise to hand over so much material wealth when called upon to do so. The father of these four ‘idle mouths,’ had done (let us say) five thousand pounds’ worth of useful work for the community. In return for this, the community had given him what amounted to a written promise to hand over, whenever called upon to do so, five thousand pounds’ worth of food, &c. Then, if he only uses one thousand pounds’ worth himself, and leaves the rest of the notes to his children, surely they have a full right to present these written promises, and to say ‘hand over the food, for which the equivalent labour has been already done.’ Now I think this case well worth stating, publicly and clearly. I should like to drive it into the heads of those Socialists who are priming our ignorant paupers with such sentiments as ‘Look at them bloated haristocrats! Doing not a stroke o’ work for theirselves, and living on the sweat of our brows!’ I should like to force them to see that the money, which those ‘haristocrats’ are spending, represents so much labour already done for the community, and whose equivalent, in material wealth, is due from the community.”

“Might not the Socialists reply ‘Much of this money does not represent honest labour at all. If you could trace it back, from owner to owner, though you might begin with several legitimate steps, such as gift, or bequeathing by will, or ‘value received,’ you would soon reach an owner who had no moral right to it, but had got it by fraud or other crimes; and of course his successors in the line would have no better right to it than he had.”

“No doubt, no doubt,” Arthur replied. “But surely that involves the logical fallacy of proving too much? It is quite as applicable to material wealth, as it is to money. If we once begin to go back beyond the fact that the present owner of certain property came by it honestly, and to ask whether any previous owner, in past ages, got it by fraud, would any property be secure?”

After a minute’s thought, I felt obliged to admit the truth of this.

“My general conclusion,” Arthur continued, “from the mere standpoint of human rights, man against man, was this—that if some wealthy ‘idle mouth,’ who has come by his money in a lawful way, even though not one atom of the labour it represents has been his own doing, chooses to spend it on his own needs, without contributing any labour to the community from whom he buys his food and clothes, that community has no right to interfere with him. But it’s quite another thing, when we come to consider the divine law. Measured by that standard, such a man is undoubtedly doing wrong, if he fails to use, for the good of those in need, the strength or the skill, that God has given him. That strength and skill do not belong to the community, to be paid to them as a debt: they do not belong to the man himself, to be used for his own enjoyment: they do belong to God, to be used according to His will; and we are not left in doubt as to what that will is. ‘Do good, and lend, hoping for nothing again.’”

“Anyhow,” I said, “an ‘idle mouth’ very often gives away a great deal in charity.”

“In so-called ‘charity,’” he corrected me. “Excuse me if I seem to speak uncharitably. I would not dream of applying the term to any individual. But I would say, generally, that a man who gratifies every fancy that occurs to him—denying himself in nothing—and merely gives to the poor some part, or even all, of his superfluous wealth, is only deceiving himself if he calls it charity.”

“But, even in giving away superfluous wealth, he may be denying himself the miser’s pleasure in hoarding?”

“I grant you that, gladly,” said Arthur. “Given that he has that morbid craving, he is doing a good deed in restraining it.”

“But, even in spending on himself,” I persisted, “our typical rich man often does good, by employing people who would otherwise be out of work: and that is often better than pauperising them by giving the money.”

“I’m glad you’ve said that!” said Arthur. “I would not like to quit the subject without exposing the two fallacies of that statement—which have gone so long uncontradicted that Society now accepts it as an axiom!”

“What are they?” I said. “I don’t even see one, myself.”

“One is merely the fallacy of ambiguity—the assumption that ‘doing good’ (that is, benefiting somebody) is necessarily a good thing to do (that is, a right thing). The other is the assumption that, if one of two specified acts is better than another, it is necessarily a good act in itself. I should like to call this the fallacy of comparison—meaning that it assumes that what is comparatively good is therefore positively good.”

“Then what is your test of a good act?”

“That it shall be our best,” Arthur confidently replied. “And even then ‘we are unprofitable servants.’ But let me illustrate the two fallacies. Nothing illustrates a fallacy so well as an extreme case, which fairly comes under it. Suppose I find two children drowning in a pond. I rush in, and save one of the children, and then walk away, leaving the other to drown. Clearly I have ‘done good,’ in saving a child’s life? But——. Again, supposing I meet an inoffensive stranger, and knock him down, and walk on. Clearly that is ‘better’ than if I had proceeded to jump upon him and break his ribs? But——”

“Those ‘buts’ are quite unanswerable,” I said. “But I should like an instance from real life.”

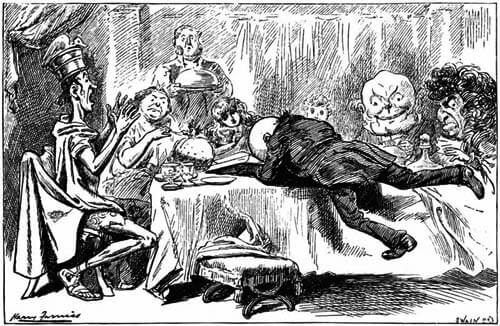

“Well, let us take one of those abominations of modern Society, a Charity-Bazaar. It’s an interesting question to think out—how much of the money, that reaches the object in view, is genuine charity; and whether even that is spent in the best way. But the subject needs regular classification, and analysis, to understand it properly.”

“I should be glad to have it analysed,” I said: “it has often puzzled me.”

“Well, if I am really not boring you. Let us suppose our Charity-Bazaar to have been organised to aid the funds of some Hospital: and that A, B, C give their services in making articles to sell, and in acting as salesmen, while X, Y, Z buy the articles, and the money so paid goes to the Hospital.

“There are two distinct species of such Bazaars: one, where the payment exacted is merely the market-value of the goods supplied, that is, exactly what you would have to pay at a shop: the other, where fancy-prices are asked. We must take these separately.

“First, the ‘market-value’ case. Here A, B, C are exactly in the same position as ordinary shopkeepers; the only difference being that they give the proceeds to the Hospital. Practically, they are giving their skilled labour for the benefit of the Hospital. This seems to me to be genuine charity. And I don’t see how they could use it better. But X, Y, Z, are exactly in the same position as any ordinary purchasers of goods. To talk of ‘charity’ in connection with their share of the business, is sheer nonsense. Yet they are very likely to do so.

“Secondly, the case of ‘fancy-prices.’ Here I think the simplest plan is to divide the payment into two parts, the ‘market-value’ and the excess over that. The ‘market-value’ part is on the same footing as in the first case: the excess is all we have to consider. Well, A, B, C do not earn it; so we may put them out of the question: it is a gift, from X, Y, Z, to the Hospital. And my opinion is that it is not given in the best way: far better buy what they choose to buy, and give what they choose to give, as two separate transactions: then there is some chance that their motive in giving may be real charity, instead of a mixed motive—half charity, half self-pleasing. ‘The trail of the serpent is over it all.’ And therefore it is that I hold all such spurious ‘Charities’ in utter abomination!” He ended with unusual energy, and savagely beheaded, with his stick, a tall thistle at the road-side, behind which I was startled to see Sylvie and Bruno standing. I caught at his arm, but too late to stop him. Whether the stick reached them, or not, I could not feel sure: at any rate they took not the smallest notice of it, but smiled gaily, and nodded to me; and I saw at once that they were only visible to me: the ‘eerie’ influence had not reached to Arthur.

“Why did you try to save it?” he said. “That’s not the wheedling Secretary of a Charity-Bazaar! I only wish it were!” he added grimly.

“Doos oo know, that stick went right froo my head!” said Bruno. (They had run round to me by this time, and each had secured a hand.) “Just under my chin! I are glad I aren’t a thistle!”

“Well, we’ve threshed that subject out, anyhow!” Arthur resumed. “I’m afraid I’ve been talking too much, for your patience and for my strength. I must be turning soon. This is about the end of my tether.”

“Take, O boatman, thrice thy fee;

Take, I give it willingly;

For, invisible to thee,

Spirits twain have crossed with me!”

I quoted, involuntarily.

“For utterly inappropriate and irrelevant quotations,” laughed Arthur, “you are ‘ekalled by few, and excelled by none’!” And we strolled on.

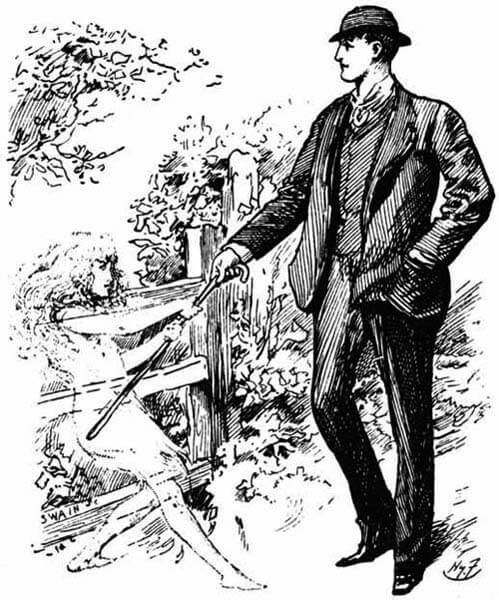

As we passed the head of the lane that led down to the beach, I noticed a single figure, moving slowly along it, seawards. She was a good way off, and had her back to us: but it was Lady Muriel, unmistakably. Knowing that Arthur had not seen her, as he had been looking, in the other direction, at a gathering rain-cloud, I made no remark, but tried to think of some plausible pretext for sending him back by the sea.

The opportunity instantly presented itself. “I’m getting tired,” he said. “I don’t think it would be prudent to go further. I had better turn here.”

I turned with him, for a few steps, and as we again approached the head of the lane, I said, as carelessly as I could, “Don’t go back by the road. It’s too hot and dusty. Down this lane, and along the beach, is nearly as short; and you’ll get a breeze off the sea.”

“Yes, I think I will,” Arthur began; but at that moment we came into sight of Lady Muriel, and he checked himself. “No, it’s too far round. Yet it certainly would be cooler——” He stood, hesitating, looking first one way and then the other—a melancholy picture of utter infirmity of purpose!

How long this humiliating scene would have continued, if I had been the only external influence, it is impossible to say; for at this moment Sylvie, with a swift decision worthy of Napoleon himself, took the matter into her own hands. “You go and drive her, up this way,” she said to Bruno. “I’ll get him along!” And she took hold of the stick that Arthur was carrying, and gently pulled him down the lane.

He was totally unconscious that any will but his own was acting on the stick, and appeared to think it had taken a horizontal position simply because he was pointing with it. “Are not those orchises under the hedge there?” he said. “I think that decides me. I’ll gather some as I go along.”

Meanwhile Bruno had run on beyond Lady Muriel, and, with much jumping about and shouting (shouts audible to no one but Sylvie and myself), much as if he were driving sheep, he managed to turn her round and make her walk, with eyes demurely cast upon the ground, in our direction.

The victory was ours! And, since it was evident that the lovers, thus urged together, must meet in another minute, I turned and walked on, hoping that Sylvie and Bruno would follow my example, as I felt sure that the fewer the spectators the better it would be for Arthur and his good angel.

“And what sort of meeting was it?” I wondered, as I paced dreamily on.

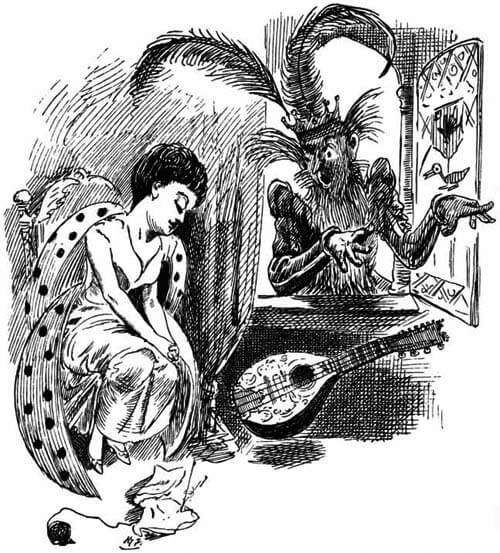

Chapter IV. The Dog-King.

“They shooked hands,” said Bruno, who was trotting at my side, in answer to the unspoken question.

“And they looked ever so pleased!” Sylvie added from the other side.

“Well, we must get on, now, as quick as we can,” I said. “If only I knew the best way to Hunter’s farm!”

“They’ll be sure to know in this cottage,” said Sylvie.

“Yes, I suppose they will. Bruno, would you run in and ask?”

Sylvie stopped him, laughingly, as he ran off. “Wait a minute,” she said. “I must make you visible first, you know.”

“And audible too, I suppose?” I said, as she took the jewel, that hung round her neck, and waved it over his head, and touched his eyes and lips with it.

“Yes,” said Sylvie: “and once, do you know, I made him audible, and forgot to make him visible! And he went to buy some sweeties in a shop. And the man was so frightened! A voice seemed to come out of the air, ‘Please, I want two ounces of barley-sugar drops!’ And a shilling came bang down upon the counter! And the man said ‘I ca’n’t see you!’ And Bruno said ‘It doosn’t sinnify seeing me, so long as oo can see the shilling!’ But the man said he never sold barley-sugar drops to people he couldn’t see. So we had to—Now, Bruno, you’re ready!” And away he trotted.

Sylvie spent the time, while we were waiting for him, in making herself visible also. “It’s rather awkward, you know,” she explained to me, “when we meet people, and they can see one of us, and ca’n’t see the other!”

In a minute or two Bruno returned, looking rather disconsolate. “He’d got friends with him, and he were cross!” he said. “He asked me who I were. And I said ‘I’m Bruno: who is these peoples?’ And he said ‘One’s my half-brother, and t’other’s my half-sister: and I don’t want no more company! Go along with yer!’ And I said ‘I ca’n’t go along wizout mine self!’ And I said ‘Oo shouldn’t have bits of peoples lying about like that! It’s welly untidy!’ And he said ‘Oh, don’t talk to me!’ And he pushted me outside! And he shutted the door!”

“And you never asked where Hunter’s farm was?” queried Sylvie.

“Hadn’t room for any questions,” said Bruno. “The room were so crowded.”

“Three people couldn’t crowd a room,” said Sylvie.

“They did, though,” Bruno persisted. “He crowded it most. He’s such a welly thick man—so as oo couldn’t knock him down.”

I failed to see the drift of Bruno’s argument. “Surely anybody could be knocked down,” I said: “thick or thin wouldn’t matter.”

“Oo couldn’t knock him down,” said Bruno. “He’s more wider than he’s high: so, when he’s lying down, he’s more higher than when he’s standing: so a-course oo couldn’t knock him down!”

“Here’s another cottage,” I said: “I’ll ask the way, this time.”

There was no need to go in, this time, as the woman was standing in the doorway, with a baby in her arms, talking to a respectably dressed man—a farmer, as I guessed—who seemed to be on his way to the town.

“—and when there’s drink to be had,” he was saying, “he’s just the worst o’ the lot, is your Willie. So they tell me. He gets fairly mad wi’ it!”

“I’d have given ’em the lie to their faces, a twelvemonth back!” the woman said in a broken voice. “But a’ canna noo! A’ canna noo!” She checked herself, on catching sight of us, and hastily retreated into the house, shutting the door after her.

“Perhaps you can tell me where Hunter’s farm is?” I said to the man, as he turned away from the house.

“I can that, Sir!” he replied with a smile. “I’m John Hunter hissel, at your sarvice. It’s nobbut half a mile further—the only house in sight, when you get round bend o’ the road yonder. You’ll find my good woman within, if so be you’ve business wi’ her. Or mebbe I’ll do as well?”

“Thanks,” I said. “I want to order some milk. Perhaps I had better arrange it with your wife?”

“Aye,” said the man. “She minds all that. Good day t’ye, Master—and to your bonnie childer, as well!” And he trudged on.

“He should have said ‘child,’ not ‘childer’,” said Bruno. “Sylvie’s not a childer!”

“He meant both of us,” said Sylvie.

“No, he didn’t!” Bruno persisted. “’cause he said ‘bonnie’, oo know!”

“Well, at any rate he looked at us both,” Sylvie maintained.

“Well, then he must have seen we’re not both bonnie!” Bruno retorted. “A-course I’m much uglier than oo! Didn’t he mean Sylvie, Mister Sir?” he shouted over his shoulder, as he ran off.

But there was no use in replying, as he had already vanished round the bend of the road. When we overtook him he was climbing a gate, and was gazing earnestly into the field, where a horse, a cow, and a kid were browsing amicably together. “For its father, a Horse,” he murmured to himself. “For its mother, a Cow. For their dear little child, a little Goat, is the most curiousest thing I ever seen in my world!”

“Bruno’s World!” I pondered. “Yes, I suppose every child has a world of his own—and every man, too, for the matter of that. I wonder if that’s the cause for all the misunderstanding there is in Life?”

“That must be Hunter’s farm!” said Sylvie, pointing to a house on the brow of the hill, led up to by a cart-road. “There’s no other farm in sight, this way; and you said we must be nearly there by this time.”

I had thought it, while Bruno was climbing the gate, but I couldn’t remember having said it. However, Sylvie was evidently in the right. “Get down, Bruno,” I said, “and open the gate for us.”

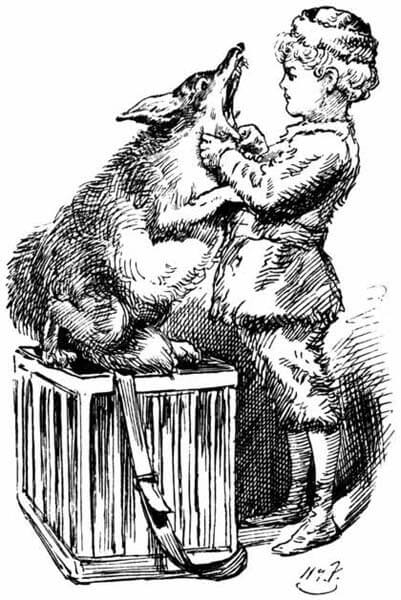

“It’s a good thing we’s with oo, isn’t it, Mister Sir?” said Bruno, as we entered the field. “That big dog might have bited oo, if oo’d been alone! Oo needn’t be flightened of it!” he whispered, clinging tight to my hand to encourage me. “It aren’t fierce!”

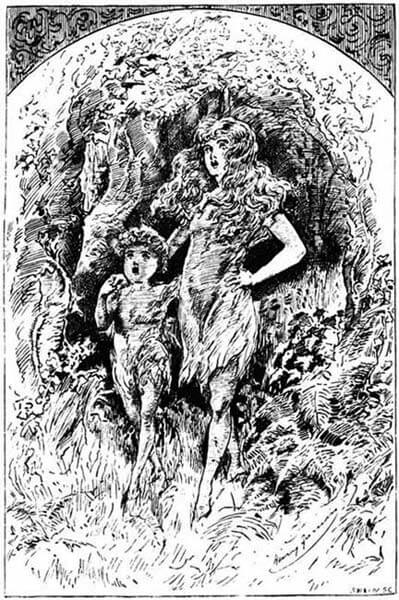

“Fierce!” Sylvie scornfully echoed, as the dog—a magnificent Newfoundland—that had come galloping down the field to meet us, began curveting round us, in gambols full of graceful beauty, and welcoming us with short joyful barks. “Fierce! Why, it’s as gentle as a lamb! It’s—why, Bruno, don’t you know it? It’s——”

“So it are!” cried Bruno, rushing forwards and throwing his arms round its neck. “Oh, you dear dog!” And it seemed as if the two children would never have done hugging and stroking it.

“And how ever did he get here?” said Bruno. “Ask him, Sylvie. I doosn’t know how.”

And then began an eager talk in Doggee, which of course was lost upon me; and I could only guess, when the beautiful creature, with a sly glance at me, whispered something in Sylvie’s ear, that I was now the subject of conversation. Sylvie looked round laughingly.

“He asked me who you are,” she explained. “And I said ‘He’s our friend.’ And he said ‘What’s his name?’ And I said ‘It’s Mister Sir.’ And he said ‘Bosh!’”

“What is ‘Bosh!’ in Doggee?” I enquired.

“It’s the same as in English,” said Sylvie. “Only, when a dog says it, it’s a sort of a whisper, that’s half a cough and half a bark. Nero, say ‘Bosh!’”

And Nero, who had now begun gamboling round us again, said “Bosh!” several times; and I found that Sylvie’s description of the sound was perfectly accurate.

“I wonder what’s behind this long wall?” I said, as we walked on.

“It’s the Orchard,” Sylvie replied, after a consultation with Nero. “See, there’s a boy getting down off the wall, at that far corner. And now he’s running away across the field. I do believe he’s been stealing the apples!”

Bruno set off after him, but returned to us in a few moments, as he had evidently no chance of overtaking the young rascal.

“I couldn’t catch him!” he said. “I wiss I’d started a little sooner. His pockets was full of apples!”

The Dog-King looked up at Sylvie, and said something in Doggee.

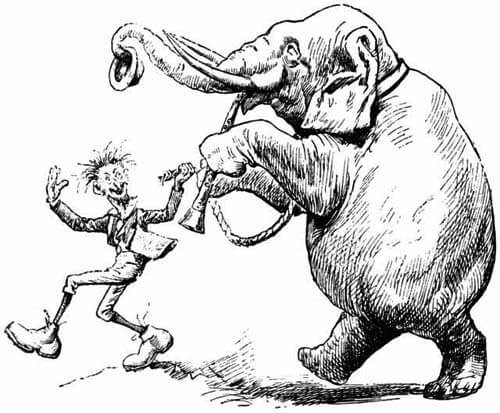

“Why, of course you can!” Sylvie exclaimed. “How stupid not to think of it! Nero’ll hold him for us, Bruno! But I’d better make him invisible, first.” And she hastily got out the Magic Jewel, and began waving it over Nero’s head, and down along his back.

“That’ll do!” cried Bruno, impatiently. “After him, good Doggie!”

“Oh, Bruno!” Sylvie exclaimed reproachfully. “You shouldn’t have sent him off so quick! I hadn’t done the tail!”

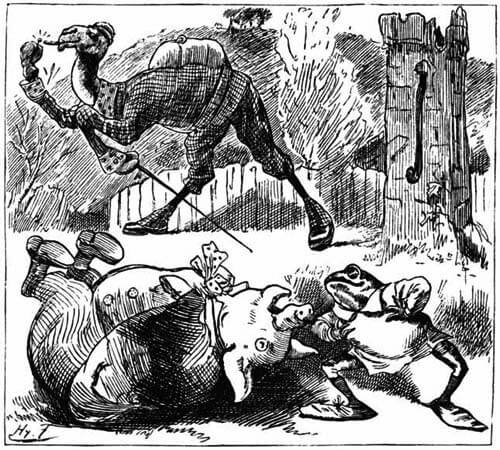

Meanwhile Nero was coursing like a greyhound down the field: so at least I concluded from all I could see of him—the long feathery tail, which floated like a meteor through the air—and in a very few seconds he had come up with the little thief.

“He’s got him safe, by one foot!” cried Sylvie, who was eagerly watching the chase. “Now there’s no hurry, Bruno!”

So we walked, quite leisurely, down the field, to where the frightened lad stood. A more curious sight I had seldom seen, in all my ‘eerie’ experiences. Every bit of him was in violent action, except the left foot, which was apparently glued to the ground—there being nothing visibly holding it: while, at some little distance, the long feathery tail was waving gracefully from side to side, showing that Nero, at least, regarded the whole affair as nothing but a magnificent game of play.

“What’s the matter with you?” I said, as gravely as I could.

“Got the crahmp in me ahnkle!” the thief groaned in reply. “An’ me fut’s gone to sleep!” And he began to blubber aloud.

“Now, look here!” Bruno said in a commanding tone, getting in front of him. “Oo’ve got to give up those apples!”

The lad glanced at me, but didn’t seem to reckon my interference as worth anything. Then he glanced at Sylvie: she clearly didn’t count for very much, either. Then he took courage. “It’ll take a better man than any of yer to get ’em!” he retorted defiantly.

Sylvie stooped and patted the invisible Nero. “A little tighter!” she whispered. And a sharp yell from the ragged boy showed how promptly the Dog-King had taken the hint.

“What’s the matter now?” I said. “Is your ankle worse?”

“And it’ll get worse, and worse, and worse,” Bruno solemnly assured him, “till oo gives up those apples!”

Apparently the thief was convinced of this at last, and he sulkily began emptying his pockets of the apples. The children watched from a little distance, Bruno dancing with delight at every fresh yell extracted from Nero’s terrified prisoner.

“That’s all,” the boy said at last.

“It isn’t all!” cried Bruno. “There’s three more in that pocket!”

Another hint from Sylvie to the Dog-King—another sharp yell from the thief, now convicted of lying also—and the remaining three apples were surrendered.

“Let him go, please,” Sylvie said in Doggee, and the lad limped away at a great pace, stooping now and then to rub the ailing ankle, in fear, seemingly, that the ‘crahmp’ might attack it again.

Bruno ran back, with his booty, to the orchard wall, and pitched the apples over it one by one. “I’s welly afraid some of them’s gone under the wrong trees!” he panted, on overtaking us again.

“The wrong trees!” laughed Sylvie. “Trees ca’n’t do wrong! There’s no such things as wrong trees!”

“Then there’s no such things as right trees, neither!” cried Bruno. And Sylvie gave up the point.

“Wait a minute, please!” she said to me. “I must make Nero visible, you know!”

“No, please don’t!” cried Bruno, who had by this time mounted on the Royal back, and was twisting the Royal hair into a bridle. “It’ll be such fun to have him like this!”

“Well, it does look funny,” Sylvie admitted, and led the way to the farm-house, where the farmer’s wife stood, evidently much perplexed at the weird procession now approaching her. “It’s summat gone wrong wi’ my spectacles, I doubt!” she murmured, as she took them off, and began diligently rubbing them with a corner of her apron.

Meanwhile Sylvie had hastily pulled Bruno down from his steed, and had just time to make His Majesty wholly visible before the spectacles were resumed.

All was natural, now; but the good woman still looked a little uneasy about it. “My eyesight’s getting bad,” she said, “but I see you now, my darlings! You’ll give me a kiss, wo’n’t you?”

Bruno got behind me, in a moment: however Sylvie put up her face, to be kissed, as representative of both, and we all went in together.

Chapter V. Matilda Jane.

“Come to me, my little gentleman,” said our hostess, lifting Bruno into her lap, “and tell me everything.”

“I ca’n’t,” said Bruno. “There wouldn’t be time. Besides, I don’t know everything.”

The good woman looked a little puzzled, and turned to Sylvie for help. “Does he like riding?” she asked.

“Yes, I think so,” Sylvie gently replied. “He’s just had a ride on Nero.”

“Ah, Nero’s a grand dog, isn’t he? Were you ever outside a horse, my little man?”

“Always!” Bruno said with great decision. “Never was inside one. Was oo?”

Here I thought it well to interpose, and to mention the business on which we had come, and so relieved her, for a few minutes, from Bruno’s perplexing questions.

“And those dear children will like a bit of cake, I’ll warrant!” said the farmer’s hospitable wife, when the business was concluded, as she opened her cupboard, and brought out a cake. “And don’t you waste the crust, little gentleman!” she added, as she handed a good slice of it to Bruno. “You know what the poetry-book says about wilful waste?”

“No, I don’t,” said Bruno. “What doos he say about it?”

“Tell him, Bessie!” And the mother looked down, proudly and lovingly, on a rosy little maiden, who had just crept shyly into the room, and was leaning against her knee. “What’s that your poetry-book says about wilful waste?”

“For wilful waste makes woeful want,” Bessie recited, in an almost inaudible whisper: “and you may live to say ‘How much I wish I had the crust that then I threw away!’”

“Now try if you can say it, my dear! For wilful——”

“For wifful—sumfinoruvver—” Bruno began, readily enough; and then there came a dead pause. “Ca’n’t remember no more!”

“Well, what do you learn from it, then? You can tell us that, at any rate?”

Bruno ate a little more cake, and considered: but the moral did not seem to him to be a very obvious one.

“Always to——” Sylvie prompted him in a whisper.

“Always to——” Bruno softly repeated: and then, with sudden inspiration, “always to look where it goes to!”

“Where what goes to, darling?”

“Why the crust, a course!” said Bruno. “Then, if I lived to say ‘How much I wiss I had the crust—’ (and all that), I’d know where I frew it to!”

This new interpretation quite puzzled the good woman. She returned to the subject of ‘Bessie.’ “Wouldn’t you like to see Bessie’s doll, my dears! Bessie, take the little lady and gentleman to see Matilda Jane!”

Bessie’s shyness thawed away in a moment. “Matilda Jane has just woke up,” she stated, confidentially, to Sylvie. “Wo’n’t you help me on with her frock? Them strings is such a bother to tie!”

“I can tie strings,” we heard, in Sylvie’s gentle voice, as the two little girls left the room together. Bruno ignored the whole proceeding, and strolled to the window, quite with the air of a fashionable gentleman. Little girls, and dolls, were not at all in his line.

And forthwith the fond mother proceeded to tell me (as what mother is not ready to do?) of all Bessie’s virtues (and vices too, for the matter of that) and of the many fearful maladies which, notwithstanding those ruddy cheeks and that plump little figure, had nearly, time and again, swept her from the face of the earth.

When the full stream of loving memories had nearly run itself out, I began to question her about the working men of that neighbourhood, and specially the ‘Willie,’ whom we had heard of at his cottage. “He was a good fellow once,” said my kind hostess: “but it’s the drink has ruined him! Not that I’d rob them of the drink—it’s good for the most of them—but there’s some as is too weak to stand agin’ temptations: it’s a thousand pities, for them, as they ever built the Golden Lion at the corner there!”

“The Golden Lion?” I repeated.

“It’s the new Public,” my hostess explained. “And it stands right in the way, and handy for the workmen, as they come back from the brickfields, as it might be to-day, with their week’s wages. A deal of money gets wasted that way. And some of ’em gets drunk.”

“If only they could have it in their own houses—” I mused, hardly knowing I had said the words out loud.

“That’s it!” she eagerly exclaimed. It was evidently a solution, of the problem, that she had already thought out. “If only you could manage, so’s each man to have his own little barrel in his own house—there’d hardly be a drunken man in the length and breadth of the land!”

And then I told her the old story—about a certain cottager who bought himself a little barrel of beer, and installed his wife as bar-keeper: and how, every time he wanted his mug of beer, he regularly paid her over the counter for it: and how she never would let him go on ‘tick,’ and was a perfectly inflexible bar-keeper in never letting him have more than his proper allowance: and how, every time the barrel needed refilling, she had plenty to do it with, and something over for her money-box: and how, at the end of the year, he not only found himself in first-rate health and spirits, with that undefinable but quite unmistakeable air which always distinguishes the sober man from the one who takes ‘a drop too much,’ but had quite a box full of money, all saved out of his own pence!

“If only they’d all do like that!” said the good woman, wiping her eyes, which were overflowing with kindly sympathy. “Drink hadn’t need to be the curse it is to some——”

“Only a curse,” I said, “when it is used wrongly. Any of God’s gifts may be turned into a curse, unless we use it wisely. But we must be getting home. Would you call the little girls? Matilda Jane has seen enough of company, for one day, I’m sure!”

“I’ll find ’em in a minute,” said my hostess, as she rose to leave the room. “Maybe that young gentleman saw which way they went?”

“Where are they, Bruno?” I said.

“They ain’t in the field,” was Bruno’s rather evasive reply, “’cause there’s nothing but pigs there, and Sylvie isn’t a pig. Now don’t imperrupt me any more, ’cause I’m telling a story to this fly; and it won’t attend!”

“They’re among the apples, I’ll warrant ’em!” said the Farmer’s wife. So we left Bruno to finish his story, and went out into the orchard, where we soon came upon the children, walking sedately side by side, Sylvie carrying the doll, while little Bess carefully shaded its face, with a large cabbage-leaf for a parasol.

As soon as they caught sight of us, little Bess dropped her cabbage-leaf and came running to meet us, Sylvie following more slowly, as her precious charge evidently needed great care and attention.

“I’m its Mamma, and Sylvie’s the Head-Nurse,” Bessie explained: “and Sylvie’s taught me ever such a pretty song, for me to sing to Matilda Jane!”

“Let’s hear it once more, Sylvie,” I said, delighted at getting the chance I had long wished for, of hearing her sing. But Sylvie turned shy and frightened in a moment. “No, please not!” she said, in an earnest ‘aside’ to me. “Bessie knows it quite perfect now. Bessie can sing it!”

“Aye, aye! Let Bessie sing it!” said the proud mother. “Bessie has a bonny voice of her own,” (this again was an ‘aside’ to me) “though I say it as shouldn’t!”

Bessie was only too happy to accept the ‘encore.’ So the plump little Mamma sat down at our feet, with her hideous daughter reclining stiffly across her lap (it was one of a kind that wo’n’t sit down, under any amount of persuasion), and, with a face simply beaming with delight, began the lullaby, in a shout that ought to have frightened the poor baby into fits. The Head-Nurse crouched down behind her, keeping herself respectfully in the back-ground, with her hands on the shoulders of her little mistress, so as to be ready to act as Prompter, if required, and to supply ‘each gap in faithless memory void.’

The shout, with which she began, proved to be only a momentary effort. After a very few notes, Bessie toned down, and sang on in a small but very sweet voice. At first her great black eyes were fixed on her mother, but soon her gaze wandered upwards, among the apples, and she seemed to have quite forgotten that she had any other audience than her Baby, and her Head-Nurse, who once or twice supplied, almost inaudibly, the right note, when the singer was getting a little ‘flat.’

“Matilda Jane, you never look

At any toy or picture-book:

I show you pretty things in vain—

You must be blind, Matilda Jane!

“I ask you riddles, tell you tales,

But all our conversation fails:

You never answer me again—

I fear you’re dumb, Matilda Jane!

“Matilda, darling, when I call,

You never seem to hear at all:

I shout with all my might and main—

But you’re so deaf, Matilda Jane!

“Matilda Jane, you needn’t mind;

For, though you’re deaf, and dumb, and blind,

There’s some one loves you, it is plain—

And that is me, Matilda Jane!”

She sang three of the verses in a rather perfunctory style, but the last stanza evidently excited the little maiden. Her voice rose, ever clearer and louder: she had a rapt look on her face, as if suddenly inspired, and, as she sang the last few words, she clasped to her heart the inattentive Matilda Jane.

“Kiss it now!” prompted the Head-Nurse. And in a moment the simpering meaningless face of the Baby was covered with a shower of passionate kisses.

“What a bonny song!” cried the Farmer’s wife. “Who made the words, dearie?”

“I—I think I’ll look for Bruno,” Sylvie said demurely, and left us hastily. The curious child seemed always afraid of being praised, or even noticed.

“Sylvie planned the words,” Bessie informed us, proud of her superior information: “and Bruno planned the music—and I sang it!” (this last circumstance, by the way, we did not need to be told).

So we followed Sylvie, and all entered the parlour together. Bruno was still standing at the window, with his elbows on the sill. He had, apparently, finished the story that he was telling to the fly, and had found a new occupation. “Don’t imperrupt!” he said as we came in. “I’m counting the Pigs in the field!”

“How many are there?” I enquired.

“About a thousand and four,” said Bruno.

“You mean ‘about a thousand,’” Sylvie corrected him. “There’s no good saying ‘and four’: you ca’n’t be sure about the four!”

“And you’re as wrong as ever!” Bruno exclaimed triumphantly. “It’s just the four I can be sure about; ’cause they’re here, grubbling under the window! It’s the thousand I isn’t pruffickly sure about!”

“But some of them have gone into the sty,” Sylvie said, leaning over him to look out of the window.

“Yes,” said Bruno; “but they went so slowly and so fewly, I didn’t care to count them.”

“We must be going, children,” I said. “Wish Bessie good-bye.” Sylvie flung her arms round the little maiden’s neck, and kissed her: but Bruno stood aloof, looking unusually shy. (“I never kiss nobody but Sylvie!” he explained to me afterwards.) The farmer’s wife showed us out: and we were soon on our way back to Elveston.

“And that’s the new public-house that we were talking about, I suppose?” I said, as we came in sight of a long low building, with the words ‘The Golden Lion’ over the door.

“Yes, that’s it,” said Sylvie. “I wonder if her Willie’s inside? Run in, Bruno, and see if he’s there.”

I interposed, feeling that Bruno was, in a sort of way, in my care. “That’s not a place to send a child into.” For already the revelers were getting noisy: and a wild discord of singing, shouting, and meaningless laughter came to us through the open windows.

“They wo’n’t see him, you know,” Sylvie explained. “Wait a minute, Bruno!” She clasped the jewel, that always hung round her neck, between the palms of her hands, and muttered a few words to herself. What they were I could not at all make out, but some mysterious change seemed instantly to pass over us. My feet seemed to me no longer to press the ground, and the dream-like feeling came upon me, that I was suddenly endowed with the power of floating in the air. I could still just see the children: but their forms were shadowy and unsubstantial, and their voices sounded as if they came from some distant place and time, they were so unreal. However, I offered no further opposition to Bruno’s going into the house. He was back again in a few moments. “No, he isn’t come yet,” he said. “They’re talking about him inside, and saying how drunk he was last week.”

While he was speaking, one of the men lounged out through the door, a pipe in one hand and a mug of beer in the other, and crossed to where we were standing, so as to get a better view along the road. Two or three others leaned out through the open window, each holding his mug of beer, with red faces and sleepy eyes. “Canst see him, lad?” one of them asked.

“I dunnot know,” the man said, taking a step forwards, which brought us nearly face to face. Sylvie hastily pulled me out of his way. “Thanks, child,” I said. “I had forgotten he couldn’t see us. What would have happened if I had staid in his way?”

“I don’t know,” Sylvie said gravely. “It wouldn’t matter to us; but you may be different.” She said this in her usual voice, but the man took no sort of notice, though she was standing close in front of him, and looking up into his face as she spoke.

“He’s coming now!” cried Bruno, pointing down the road.

“He be a-coomin noo!” echoed the man, stretching out his arm exactly over Bruno’s head, and pointing with his pipe.

“Then chorus agin!” was shouted out by one of the red-faced men in the window: and forthwith a dozen voices yelled, to a harsh discordant melody, the refrain:—

“There’s him, an’ yo’ an’ me,

Roarin’ laddies!

We loves a bit o spree,

Roarin’ laddies we,

Roarin’ laddies

Roarin’ laddies!”

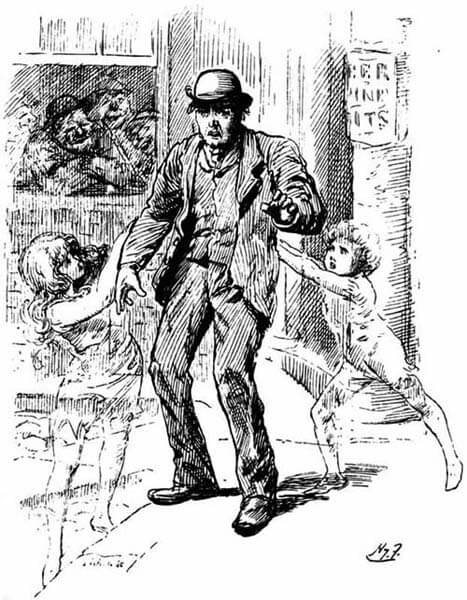

The man lounged back again to the house, joining lustily in the chorus as he went: so that only the children and I were in the road when ‘Willie’ came up.

Chapter VI. Willie’s Wife.

He made for the door of the public-house, but the children intercepted him. Sylvie clung to one arm; while Bruno, on the opposite side, was pushing him with all his strength, with many inarticulate cries of “Gee-up! Gee-back! Woah then!” which he had picked up from the waggoners.

‘Willie’ took not the least notice of them: he was simply conscious that something had checked him: and, for want of any other way of accounting for it, he seemed to regard it as his own act.

“I wunnut coom in,” he said: “not to-day.”

“A mug o’ beer wunnut hurt ’ee!” his friends shouted in chorus. “Two mugs wunnut hurt ’ee! Nor a dozen mugs!”

“Nay,” said Willie. “I’m agoan whoam.”

“What, withouten thy drink, Willie man?” shouted the others. But ‘Willie man’ would have no more discussion, and turned doggedly away, the children keeping one on each side of him, to guard him against any change in his sudden resolution.

For a while he walked on stoutly enough, keeping his hands in his pockets, and softly whistling a tune, in time to his heavy tread: his success, in appearing entirely at his ease, was almost complete; but a careful observer would have noted that he had forgotten the second part of the air, and that, when it broke down, he instantly began it again, being too nervous to think of another, and too restless to endure silence.

It was not the old fear that possessed him now—the old fear, that had been his dreary companion every Saturday night he could remember, as he had reeled along, steadying himself against gates and garden-palings, and when the shrill reproaches of his wife had seemed to his dazed brain only the echo of a yet more piercing voice within, the intolerable wail of a hopeless remorse: it was a wholly new fear that had come to him now: life had taken on itself a new set of colours, and was lighted up with a new and dazzling radiance, and he did not see, as yet, how his home-life, and his wife and child, would fit into the new order of things: the very novelty of it all was, to his simple mind, a perplexity and an overwhelming terror.

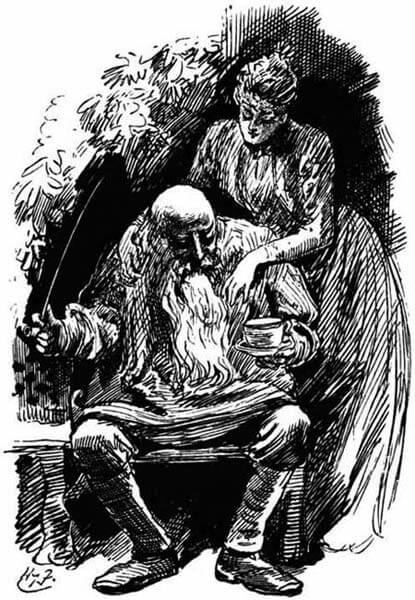

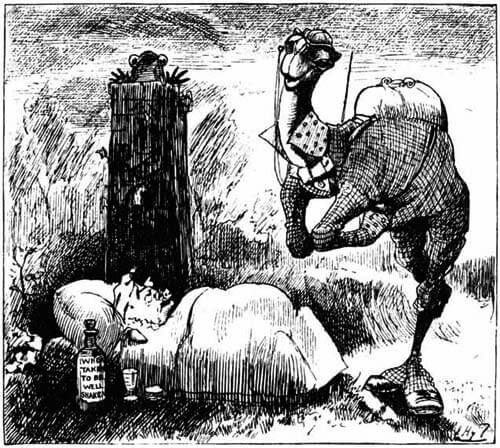

And now the tune died into sudden silence on the trembling lips, as he turned a sharp corner, and came in sight of his own cottage, where his wife stood, leaning with folded arms on the wicket-gate, and looking up the road with a pale face, that had in it no glimmer of the light of hope—only the heavy shadow of a deep stony despair.

“Fine an’ early, lad! Fine an’ early!” The words might have been words of welcoming, but oh, the bitterness of the tone in which she said it! “What brings thee from thy merry mates, and all the fiddling and the jigging? Pockets empty, I doubt? Or thou’st come, mebbe, for to see thy little one die? The bairnie’s clemmed, and I’ve nor bite nor sup to gie her. But what does thou care?” She flung the gate open, and met him with blazing eyes of fury.

The man said no word. Slowly, and with downcast eyes, he passed into the house, while she, half terrified at his strange silence, followed him in without another word; and it was not till he had sunk into a chair, with his arms crossed on the table and with drooping head, that she found her voice again.

It seemed entirely natural for us to go in with them: at another time one would have asked leave for this, but I felt, I knew not why, that we were in some mysterious way invisible, and as free to come and to go as disembodied spirits.

The child in the cradle woke up, and raised a piteous cry, which in a moment brought the children to its side: Bruno rocked the cradle, while Sylvie tenderly replaced the little head on the pillow from which it had slipped. But the mother took no heed of the cry, nor yet of the satisfied ‘coo’ that it set up when Sylvie had made it happy again: she only stood gazing at her husband, and vainly trying, with white quivering lips (I believe she thought he was mad), to speak in the old tones of shrill upbraiding that he knew so well.

“And thou’st spent all thy wages—I’ll swear thou hast—on the devil’s own drink—and thou’st been and made thysen a beast again—as thou allus dost——”

“Hasna!” the man muttered, his voice hardly rising above a whisper, as he slowly emptied his pockets on the table. “There’s th’ wage, Missus, every penny on’t.”

The woman gasped, and put one hand to her heart, as if under some great shock of surprise. “Then how’s thee gotten th’ drink?”

“Hasna gotten it,” he answered her, in a tone more sad than sullen. “I hanna touched a drop this blessed day. No!” he cried aloud, bringing his clenched fist heavily down upon the table, and looking up at her with gleaming eyes, “nor I’ll never touch another drop o’ the cursed drink—till I die—so help me God my Maker!” His voice, which had suddenly risen to a hoarse shout, dropped again as suddenly: and once more he bowed his head, and buried his face in his folded arms.

The woman had dropped upon her knees by the cradle, while he was speaking. She neither looked at him nor seemed to hear him. With hands clasped above her head, she rocked herself wildly to and fro. “Oh my God! Oh my God!” was all she said, over and over again.

Sylvie and Bruno gently unclasped her hands and drew them down—till she had an arm round each of them, though she took no notice of them, but knelt on with eyes gazing upwards, and lips that moved as if in silent thanksgiving. The man kept his face hidden, and uttered no sound: but one could see the sobs that shook him from head to foot.