Reasonings on Rubbish

“Aye, there’s the rub!” Shakespeare.

The beginning of a new periodical is always an anxious moment for the editor: the question naturally suggests itself, “What if it should fail altogether?” This, however is a fate which, we must confess, we do not by any means anticipate for this Magazine. We look forwards with confident prospection to the time when, teeming with the voluntary productions of the most gifted and talented authors and authoresses of this country, the Rectory Magazine shall draw from admiring thousands their unanimous and uncalled for plaudits! when it shall become one of the staple and essential portions of the literature of England, when infants shall lisp their first spelling-lessons out of “Reasonings on Rubbish”! “But you are wandering from your subject!” methinks I hear some fidgetty reader exclaim. We question that, good Reader: have we not been writing about our Magazine? and is it not, to all intents and purposes, Rubbish? yea veritable and unmitigated Rubbish. We would, however, make a few remarks, in the capacity of Editor. Many obliging contributors have favoured us with stories &c. in many of which a considerable amount of talent is displayed: these are, with small exception, decidedly of a juvenile cast, and we would observe that this Magazine is far from being exclusively intended for Juvenile Readers. We have therefore been compelled, with considerable pain, to reject many of them, being well asured, from what we have already seen, that their authors are perfectly competent to contribute productions of a far more aspiring nature. We would again earnestly request more assistance, otherwise we regret to state that our Magazine will inevitably die out, like an un-replenished fire.

Editor.

Thoughts on Thistles

How strange and unexpected are many of the events of life! I who in bygone years pictured to myself many a pleasing dream of future greatness, when I should be admired and sought after by all my countrymen; when monarchs should condescend to employ me, and thousands should lie prostrate at my feet; when I should tread upon flowers and gorgeous satin drapery; when my trappings should be of gold and silver, and my saddle of the richest morocco; when my food should be the choicest Indian corn, awaiting me in mangers of satin-wood—I who indulged in these delicious speculations in former days, am now browsing upon a thistle! Ah well! The vicissitudes of life are various, (as the Great Chinese philospher, Confucious, was once heard to mutter to himself in an inaudible tone when no one was near) they are very various and there is no calculating upon them! From henceforth therefore I resolve to take events as they occur, to adapt my conduct to circumstances, to endure with fortitude the blows and kicks my employers may think fit to bestow upon me, and only to repay them by the most enduring obstinacy!

Such were the thoughts of an individual of that most patient tribe of animals, a Donkey, as he quietly awaited by the roadside the return of his master with a load of coals. We beg to state without hesitation that we cordially echo them ourselves, and it only remains for us to remark that we do not intend these remarks in any offensive light, that we have no wish to make a Donkey of our reader, however much in the habit he may be of making one of himself.

Editor.

Things in General

“Scarce wert thou gone.” Scott.

The question, “What is your opinion of things in general,” has been much oftener asked than answered: it has been so long and so constantly bandied about among small wits that we almost fear to write on so trite a subject. It is our intention on the present occasion to attempt something like an answer to this difficult question. We know that whatever we can see, handle, or think about is a thing, and if the question were confined to some particular thing, as, “What is your opinion of yesterday’s gooseberry pudding?” or, “What is your opinion of my new hat?” we could answer, “Never saw a worser,” or “A shocking bad ’un,” as the case might be, with the utmost confidence and readiness, but the case is changed when the question is indefinitely extended, for our opinions of different things are of course as different as the things themselves, and it would seem impossible to combine all these in one. If the question had been, “What are your opinions of things in general?” an answer might be given, but it would take volumes to express it. After mature consideration, the only way we can see out of this difficulty is this: as it can by no possibility affect or concern the questioner what your opinion may be, the best and most satisfactory answer to the question appears to be, to ask in a stern and reproachful tone of voice, “What’s that to you?”

Editor.

Anon

Rust

“The knights are dust,

‘and their good swords rust.”

Rubigo, or rust is that sand-couloured powdery covering which appears on iron after exposure to damp; it appears too on various other metals under different names such as verdigris on copper &cc; it never extends beyond a certain depth, and when once formed, it protects the metal underneath, and keeps it from the effects of the atmosphere.

Such is the philosophical definition of rust, and as such, the term is only applicable to metals, but in a metaphorical sense, it’s application is more widely extended. Thus there may be a rust of the mind or of the intellect, and there is no fate which we dread more for our magazine than that it should become rusty. We would have it’s wheels run smoothly on, the axletrees well oiled by a copious and constant stream of contributions, the dust of stupidity cleared away by the rapidly-moving fan of wit, and all obstacles and impediments removed from it’s course by the zeal and attention of it’s supporters. And yet, successful as our Magazine has hitherto been, and enthusiastically as it has been received, the fate we have been dreading for it does not seem to be very far distant. We opened our Editor’s box this morning, expecting of course to find it overflowing with contributions, and found it—our pen shudders and our ink blushes as we write—empty!

One word more on the nature of rust. As verdigris is a copper oxide &cc. &cc. &cc. so rust is usually called an iron

Editor.

But

“But let us not proceed too furious.” Goldsmith.

I would have a gorgeous and resplendent castle, fitted up in the first style of elegance and grandeur, superb gardens, full of the choicest and rarest flowers, a magnificent and extensive park, stocked with deer, abounding in natural cascades and artificial fountains, with think-foliaged avenues of trees, an enormous library, containing all the books ever printed in the world, I would have every pleasure and convenience that wealth can give, but—I can’t! Alas! reader, how many bright visions, fairy-like castles in the air, have vanished before the all-potent influence of the little monosyllable, but! “Brill,” as Dr Johnson finely observes, “brill would be turbot, but—it can’t.” Napoleon would have conquered all the inhabitable world, England included, but—he didn’t! And we ourselves would gladly prolong this learned article to pages and pages, till our reader fell asleep through weariness, but—we can’t think of anything more to say!

Editor.

Musings on Milk

Marvellously many materials make milk! Much too many to mention. ’Tis morning, and the merry milkmaid, murmuring a melting melody, moves towards the meadow; the majestic cows move meekly to meet their mirthful mistress; now mantles in the moderate milkpail the marble milk; anon mark many minute masters and misses with measureless mouths march to their morning meat of mighty mugs! Marvellest thou not, my reader, how mankind can be so matchlessly mischievous and madly meddlesome as to molest their mild maintainers? My mind misgives me at the memory of many merciless men, who may monthly be marked in our mighty metropolis, like morbid, morbid monsters, mauling and murderously misusing the mild milch cows! Murky misanthropes! Much do they merit manicles! Methinks their manners meelly mimic mouthing moon-struck maniacs! But let us mind more mundane matters. A missive met my manuals this morning from one of the munificent ad-mirers of this Magazine; morally magnificent as it was, we have not ad-mitted it, because it militates much against the manner in which this Magazine is meant to be managed. It made us mournful, and moved us to melancholy misery, even to moaning. Let not our meaning be misunderstood or misinterpreted. The matters ad-mitted must be our ad-mirer’s own. And more, they must be new, lest our magazine merge into a monotonous, mouldy mockery of mirth. With these memorable re-marks let me conclude this matter, merely mentioning that as this manuscript is a musing (referring) to milk, we mean this Magazine to be, as much as we can make it, a-musing to all mankind!

Editor.

Ideas upon Ink

“There was a time.” Thomson.

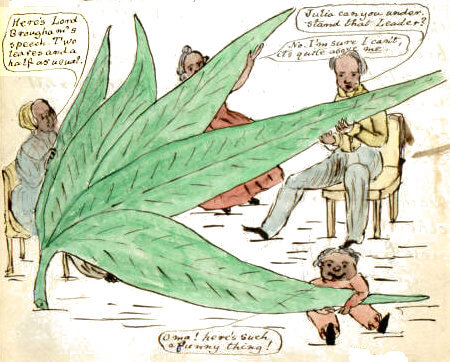

There was a time, good Reader,—you will hardly believe us, but the fact is true, nevertheless—there was a time when ink was positively unknown, when manuscripts were labouriously scratched on the leaves of the papyrus, or tablets coated with wax: imagine reading the Times on papyrus, with the leaders on the stalks, the advertisements neatly inserted between the fibres, and a double Supplement, (gratis of course) on a handsome Lotus leaf! imagine plodding through a large volume (literally) in boards, with abundance of cuts, but no plates! if you did’n’t stick in the middle, it wouldn’t be the wax’s fault. To be sure all you read therein would stick by you, and you would wax daily wiser and wiser, but still I fance you would be exceedingly bored by it. The other way would be even more voluminous, we should hear the street porters crying, “By your leaf, gentlemen, by your leaf, make way for a copy of the Queen’s Speech!” We would have you observe, good reader, the many benefits which the discovery of ink has conferred on Society. It has infinitely lightened the labours of both writer and reader: it has lessened the size of volumes, and at the same time made them more legible: it has increased a hundred-fold the literature of England, and it has procured for your delectation and instruction the publication of that inestimable periodical, the Rectory Magazine.

Here’s Lord Brougham’s speech. Two leaves and a half as usual.

Julia, can you understand that leader?

No. I’m sure I can’t, it’s quite above me.

O ma! Here’s such a funny thing!

Editor.

Twaddle on Telescopes

“Give ear.” Goldsmith.

We would not have you suppose, good reader, that because this is twaddle, it is not worth your while to peruse it. For there are many books which we are well assured you delight to read, which nevertheless are quite as much twaddle as our Magazine. Nay, perhaps even more, for many of them contain no sort of instruction or benefit for their readers, whereas by perusing our far-famed columns, you may lay in a certain store of useful and entertaining knowledge: do not smile at this assertion, we know it by experience; even while we write we feel that we are gradually rising it the scale of moral elevation, every number of the Magazine we publish elevates us two pegs, and, as certainly, elevates the attentive reader three: yes, reader, if you have carefully and with due attention read the seven numbers of this Magazine already out, you have our warrant for it that you are twenty-one pegs higher in the scale of humanity than you were when you began: that this fact admits of no doubt may be satisfactorily proved by the simple multiplication sum, “seven times three is twenty-one”: this must convince the most sceptical: argue the matter as you will, the stubborn fact remains as before. Facts are stubborn things, as Lady M— is reported to have observed to Mr F— at the conclusion of a long and tedious dispute: he is said to have replied, “then what a Fact your Ladyship must be!” but we hope for the honour of humanity he did not. We repeat reader that you are morally elevated by reading our Magazine let your heart bound at the thought, though to be sure, that direction appears to be somewhat superflous, for as the motion of the heart are acknowledged by the best anatomists to be involuntary, it will not be in your power to prevent it. And now, reader, if you suppose that we have been wandering from our subject, all we can say is, we pity your want of discernment.

Editor

Cogitations on Conclusions

“But, to conclude.”

And this is to be our last number! and we, whose unceasing occupation for a period of full six months has been the publication of this magazine,—by-the-bye it wasn’t full six months, because the Editor was at school for five months of the time—and we, are now to give up our labours, and desert the lofty task of instructing & entertaining the public in general! Ah! well! it would somewhat console us at this melancholy moment to see a fit successor fill our place—but there is none! and yet with onward glance we fancy we can discern the coming brightness of some meteor in the skies, what is it? “is that a Comet which I see before me? with tail of boundless length?” Reader, it is. Farewell.

(Editor.)