There were two brothers at Twyford school,

And when they had left the place,

It was, “Will ye learn Greek and Latin?

‘Or will ye run me a race?

‘Or will ye go up to yonder bridge,

‘And there we will angle for dace?”

“I’m too stupid for Greek and for Latin,

‘I’m too lazy by half for a race,

‘So I’ll even go up to yonder bridge,

‘And there we will angle for dace.”

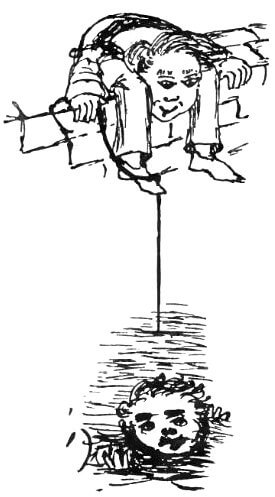

He has fitted together two joints of his rod,

And to them he has added another,

And then a great hook he took from his book,

And ran it right into his brother.

Oh much is the noise that is made among boys

When playfully pelting a pig,

But a far greater pother was made by his brother,

When flung from the top of the brigg.

The fish hurried up by the dozens,

All ready and eager to bite,

For the lad that he flung was so tender and young,

It quite gave them an appetite.

Said he, “Thus shall he wallop about

‘And the fish take him quite at their ease,

‘For me to annoy it was ever his joy,

‘Now I’ll teach him the meaning of ‘Tees’!”

The wind to his ear brought a voice,

“My brother, you didn’t had ought ter!

‘And what have I done that you think it such fun

‘To indulge in the pleasure of slaughter?

‘A good nibble or bite is my chiefest delight,

‘When I’m merely expected to see,

‘But a bite from a fish is not quite what I wish,

‘When I get it performed upon me

‘And just now here’s a swarm of dace at my arm,

‘And a perch has got hold of my knee!

‘For water my thirst was not great at the first,

‘And of fish I have quite sufficien—”

“Oh fear not!” he cried, “for whatever betide,

‘We are both in the selfsame condition!

‘I am sure that our state’s very nearly alike,

‘(Not considering the question of slaughter)

‘For I have my perch on the top of the bridge,

‘And you have your perch in the water.

‘I stick to my perch and your perch sticks to you,

‘We are really extremely alike;

‘I’ve a turn-pike up here, and I very much fear

‘You may soon have a turn with a pike.”

“Oh, grant but one wish! If I’m took by a fish,

‘(For your bait is your brother, good man!)

‘Pull him up if you like, but I hope you will strike

‘As gently as ever you can.”

“If the fish be a trout, I’m afraid there’s no doubt

‘I must strike him like lightning that’s greased;

‘If the fish be a pike, I’ll engage not to strike,

‘’Till I’ve waited ten minutes at least.”

“But in those ten minutes to desolate Fate

‘Your brother a victim may fall!”

“I’ll reduce it to five, so perhaps you’ll survive,

‘But the chance is exceedingly small.”

“Oh hard is your heart for to act such a part,

‘Is it iron, or granite, or steel?”

“Why, I really can’t say—it is many a day

‘Since my heart was accustomed to feel.

‘’Twas my heart-cherished wish for to slay many fish

‘Each day did my malice grow worse,

‘For my heart didn’t soften with doing it so often,

‘But rather, I should say, the reverse.”

“Oh would I were back at Twyford school,

‘Learning lessons in fear of the birch!”

“Nay, brother!” he cried, “for whatever betide,

‘You are better off here with your perch!

‘I am sure you’ll allow you are happier now,

‘With nothing to do but to play;

‘And this single line here, it is perfectly clear,

‘Is much better than thirty a day!

‘And as to the rod hanging over your head,

‘And apparently ready to fall,

‘That, you know, was the case, when you lived in that place,

‘So it need not be reckoned at all.

‘Do you see that old trout with a turn-up-nose snout?

‘(Just to speak on a pleasanter theme,)

‘Observe, my dear brother, our love for each other—

‘He’s the one I like best in the stream.

‘To-morrow I mean to invite him to dine,

‘(We shall all of us think it a treat,)

‘If the day should be fine, I’ll just drop him a line,

‘And we’ll settle what time we’re to meet.

‘He hasn’t been into society yet,

‘And his manners are not of the best,

‘So I think it quite fair that it should be my care,

‘To see that he’s properly dressed.”

Many words brought the wind of “cruel” and “kind,”

And that “man suffers more than the brute”:

Each several word with patience he heard,

And answered with wisdom to boot.

“What? prettier swimming in the stream,

‘Than lying all snugly and flat?

‘Do but look at that dish filled with glittering fish,

‘Has Nature a picture like that?

‘What? a higher delight to be drawn from the sight

‘Of fish full of life and of glee?

‘What a noodle you are! ’tis delightfuller far

‘To kill them than let them go free!

‘I know there are people who prate by the hour

‘Of the beauty of earth, sky, and ocean;

‘Of the birds as they fly, of the fish darting by,

‘Rejoicing in Life and in Motion.

‘As to any delight to be got from the sight,

‘It is all very well for a flat,

‘But I think it all gammon, for hooking a salmon

‘Is better than twenty of that!

‘They say that a man of a right-thinking mind

‘Will love the dumb creatures he sees—

‘What’s the use of his mind, if he’s never inclined

‘To pull a fish out of the Tees?

‘Take my friends and my home—as an outcast I’ll roam;

‘Take the money I have in the Bank—

‘It is just what I wish, but deprive me of fish,

‘And my life would indeed be a blank!”

Forth from the house his sister came,

Her brothers for to see,

But when she saw that sight of awe,

The tear stood in her ee.

“Oh what bait’s that upon your hook,

‘My brother, tell to me?”

“It is but the fantailed pigeon,

‘He would not sing for me.”

“Whoe’er would expect a pigeon to sing,

‘A simpleton he must be!

‘But a pigeon-cote is a different thing

‘To the coat that there I see!”

“Oh what bait’s that upon your hook,

‘My brother, tell to me?”

“It is but the black-capped bantam,

‘He would not dance for me.”

“And a pretty dance you are leading him now!”

In anger aswered she,

“But a bantam’s cap is a different thing

‘To the cap that there I see!”

“Oh what bait’s that upon your hook

‘Dear brother, tell to me?”

“It is my younger brother,” he cried,

“Oh woe and dole is me!

‘I’s mighty wicked, that I is!

‘Or how could such things be?

‘Farewell, farewell sweet sister,

‘I’m going o’er the sea.”

“And when will you come back again,

‘My brother, tell to me?”

“When chub is good for human food,

‘And that will never be!”

She turned herself right round about,

And her heart brake into three,

Said, “One of the two will be wet through and through,

‘And t’other’ll be late for his tea!”

Croft. 1853.