“Call you this, baching of your friends?”

Chapter I

A Conference (held on the Twentieth of March, 1873) betwixt an Angler, a Hunter, and a Professor; concerning anglings and the beautifying of Thomas his Quadrangle, The Ballad of ‘The Wandering Burgess.’

PISCATOR, VENATOR.

Piscator. My honest Scholar, we are now arrived at the place whereof I spake, and trust me, we shall have good sport. How say you? Is not this a noble Quadrangle we see around us? And be not these lawns trimly kept, and this lake marvellous clear?

Venator. So marvellous clear; good Master, and withal so brief in compass, that methinks, if any fish of a reasonable bigness were therein, we must perforce espy it. I fear me there is none.

Pisc. The less the fish, dear Scholar, the greater the skill in catching of it. Come, let’s sit down, and, while we unpack the fishing-gear, I’ll deliver a few remarks, both as to the fish to be met with hereabouts, and the properest method of fishing.

But you are to note first (for, as you are pleased to be my Scholar, it is but fitting you should imitate my habits of close observation) that the margin of this lake is so deftly fashioned that each portion thereof is at one and the same distance from that tumulus which rises in the centre.

Ven. O’ my word ’tis so! You have indeed a quick eye, dear Master, and a wondrous readiness of observing.

Pisc. Both may be yours in time, my Scholar, if with humility and patience you follow me as your model.

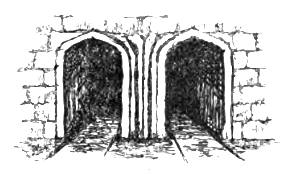

Ven. I thank you for that hope, great Master! But ere you begin your discourse, let me enquire of you one thing touching this noble Quadrangle,—Is all we see of a like antiquity? To be brief, think you that those two tall archways, that excavation in the parapet, and that quaint wooden box, belong to the ancient design of the building, or have men of our day thus sadly disfigured the place?

Pisc. I doubt not they are new, dear Scholar. For indeed I was here but a few years since, and saw naught of these things. But what book is that I see lying by the water’s edge?

Ven. A book of ancient ballads, and truly I am glad to see it, as we may herewith beguile the tediousness of the day, if our sport be poor, or if we grow aweary.

Pisc. This is well thought of. But now to business. And first I’ll tell you somewhat of the fish proper to these waters. The Commoner kinds we may let pass: for though some of them be easily Plucked forth from the water, yet are they so slow, and withal have so little in them, that they are good for nothing, unless they be crammed up to the very eyes with such stuffing as comes readiest to hand. Of these the Stickle-back, a mighty slow fish, is chiefest, and along with him you may reckon the Fluke, and divers others: all these belong to the ‘Mullet’ genus, and be good to play, though scarcely worth examination.

I will now say somewhat of the Nobler kinds, and chiefly of the Gold-fish, which is a species highly thought of, and much sought after in these parts, not only by men, but by divers birds, as for example the King -fishers: and note that wheresoever you shall see those birds assemble, and but few insects about, there shall you ever find the Gold-fish most lively and richest in flavour; but wheresoever you perceive swarms of a certain gray fly, called the Dun-fly, there the Gold-fish are ever poorer in quality, and the King-fishers seldom seen.

A good Perch may sometimes be found hereabouts: but for a good fat Plaice (which is indeed but a magnified Perch) you may search these waters in vain. They that love such dainties must needs betake them to some distant Sea.

But for the manner of fishing, I would have you note first that your line be not thicker than an ordinary bell-rope: for look you, to flog the water, as though you laid on with a flail, is most preposterous, and will surely scare the fish. And note further, that your rod must by no means exceed ten, or at the most twenty, pounds in weight, for—

Ven. Pardon me, my Master, that I thus break in on so excellent a discourse, but there now approaches us a Collegian, as I guess him to be, from whom we may haply learn the cause of these novelties we see around us. Is not that a bone which, ever as he goes, he so cautiously waves before him?

Enter PROFESSOR.

Pisc. By his reverend aspect and white hair, I guess him to be some learned Professor. I give you good day, reverend Sir! If it be not ill manners to ask it, what bone is that you bear about with you? It is, methinks, a humorous whimsy to chuse so strange a companion.

Prof. Your observation, Sir, is both anthropolitically and ambidexterously opportune: for this is indeed a Humerus I carry with me. You are, I doubt not, strangers in these parts, for else you would surely know that a Professor doth ever carry that which most aptly sets forth his Profession. Thus, the Professor of Uniform Rotation carries with him a wheelbarrow—the Professor of Graduated Scansion a ladder—and so of the rest.

Ven. It is an inconvenient and, methinks, an ill-advised custom.

Prof. Trust me, Sir, you are absolutely and amorphologically mistaken: yet time would fail me to show you wherein lies your error, for indeed I must now leave you, being bound for this great performance of music, which even at this distance salutes your ears.

Pisc. Yet, I pray you, do us one courtesy before you go: and that shall be to resolve a question, whereby my friend and I are sorely exercised.

Prof. Say on. Sir, and I will e’en answer you to the best of my poor ability.

Pisc. Briefly, then, we would ask the cause for piercing the very heart of this fair building with that uncomely tunnel, which is at once so ill-shaped, so ill-sized, and so ill-lighted.

Prof. Sir, do you know German?

Pisc. It is my grief, Sir, that I know no other tongue than mine own.

Prof. Then, Sir, my answer is this, Warum nicht?

Pisc. Alas, Sir, I understand you not.

Prof. The more the pity. For now-a-days all that is good comes from the German. Ask our men of science: they will tell you that any German book must needs surpass an English one. Aye, and even an English book, worth naught in this its native dress, shall become, when rendered into German, a valuable contribution to Science.

Ven. Sir, you much amaze me.

Prof. Nay, Sir, I’ll amaze you yet more. No learned man doth now talk, or even so much as cough, save only in German. The time has been, I doubt not, when an honest English ‘Hem!’ was held enough, both to clear the voice and rouse the attention of the company, but now-a-days no man of Science, that setteth any store by his good name, will cough otherwise than thus, Ach! Euch! Auch!

Ven. ’Tis wondrous. But, not to stay you further, wherefore do we see that ghastly gash above us, hacked, as though by some wanton school-boy, in the parapet adjoining the Hall?

Prof. Sir, do you know German?

Ven. Believe me, No.

Prof. Then, Sir, I need but ask you this, Wie befinden Sie Sich?

Ven. I doubt not. Sir, but you are in the right on’t.

Pisc. But, Sir, I will by your favour ask you one other thing, as to that unseemly box that blots the fair heavens above. Wherefore, in this grand old City, and in so conspicuous a place, do men set so hideous a thing?

Prof. Be you mad, Sir? Why this is the very climacteric and coronal of all our architectural aspirations! In all Oxford there is naught like it!

Pisc. It joys me much to hear you say so.

Prof. And, trust me, to an earnest mind, the categorical evolution of the Abstract, ideologically considered, must infallibly develop itself in the parallelepipedisation of the Concrete! And so farewell. [Exit Professor.

Pisc. He is a learned man, and methinks there is much that is sound in his reasoning.

Ven. It is all sound, as it seems to me. But how say you? Shall I read you one of these ballads? Here is one called ‘The Wandering Burgess,’ which (being forsooth a dumpish ditty) may well suit the ears of us whose eyes are oppressed with so dire a spectacle.

Pisc. Read on, good Scholar, and I will bait our hooks the while.

[Venator readeth

The Wandering Burgess.

Our Willie had been sae lang awa’

Frae bonnie Oxford toon,

The townsfolk they were greeting a’

As they went up and doon.

He hadna been gane a year, a year,

A year but barely ten,

When word cam unto Oxford toon.

Our Willie wad come agen.

Willie he stude at Thomas his Gate,

And made a lustie din;

And who so blithe as the gate-porter

To rise and let him in?

‘Now enter Willie, now enter Willie,

And look around the place.

And see the pain that we have ta’en

Thomas his Quad to grace.’

The first look that our Willie cast,

He leuch loud laughters three,

The neist look that our Willie cast,

The tear blindit his e’e.

Sae square and stark the Tea-chest frowned

Athwart the upper air,

But when the Trench our Willie saw,

He thocht the Tea-chest fair.

Sae murderous-deep the Trench did gape

The parapet aboon.

But when the Tunnel Willie saw.

He loved the Trench eftsoon.

’Twas mirk beneath the tane archway,

’Twas mirk beneath the tither;

Ye wadna ken a man therein.

Though it were your ain dear brither.

He turned him round and round about.

And looked upon the Three;

And dismal grew his countenance.

And drumlie grew his e’e.

‘What cheer, what cheer, my gallant knight?’

The gate-porter ’gan say.

‘Saw ever ye sae fair a sight

As ye have seen this day?’

‘Now haud your tongue of your prating, man:

Of your prating now let me be.

For, as I’m true knight, a fouler sight

I’ll never live to see.

‘Before I’d be the ruffian dark

Who planned this ghastly show,

I’d serve as secretary’s clerk

To Ayrton or to Lowe.

‘Before I’d own the loathly thing

That Christ Church Quad reveals,

I’d serve as shoeblack’s underling

To Odger and to Beales!’

Chapter II

A Conference with one distraught: who discourseth strangely of many things.

PISCATOR, VENATOR.

Piscator. ’Tis a marvellous pleasant ballad. But look you, another Collegian draws near. I wot not of what station he is, for indeed his apparel is new to me.

Venator. It is compounded, as I take it, of the diverse dresses of a jockey, a judge, and a North American Indian.

Enter Lunatic.

Pisc. Sir, may I make bold to ask your name?

Lun. With all my heart. Sir. It is Jeeby, at your service.

Pisc. And wherefore (if I may further trouble you, being as you see a stranger) do you wear so gaudy, but withal so ill-assorted, a garb?

Lun. Why, Sir, I’ll tell you. Do you read the Morning Post?

Pisc. Alas, Sir, I do not.

Lun. ’Tis pity of your life you do not. For, look you, not to read the Post, and not to know the newest and most commended fashions, are but one and the same thing. And yet this raiment, that I wear, is not the newest fashion. No, nor has it ever been, nor will it ever be, the fashion.

Ven. I can well believe it.

Lun. And therefore ’tis. Sir, that I wear it. ’Tis but a badge of greatness. My deeds you see around you. Si monumentum quæris, circumspice! You know Latin?

Ven. Not I, Sir! It shames me to say it.

Lun. You are then (let me roundly tell you) monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademptum!

Ven. Sir, you may tell it me roundly—or, if you list, squarely—or again, triangularly. But if, as you affirm, I see your deeds around me, I would fain know which they be.

Lun. Aloft, Sir, stands the first and chiefest! That soaring minaret! That gorgeous cupola! That dreamlike effulgence of—

Ven. That wooden box?

Lun. The same. Sir! ’Tis mine!

Ven. (after a pause). Sir, it is worthy of you.

Lun. Lower now your eyes by a hairsbreadth, and straight you light upon my second deed. Oh Sir, what toil of brain, what cudgelling of forehead, what rending of locks, went to the fashioning of it!

Ven. Mean you that newly-made gap?

Lun. I do, Sir. ’Tis mine!

Ven. (after a long pause). What else, Sir? I would fain know the worst.

Lun. (wildly). It comes, it comes! My third great deed! Lend, lend your ears—your nose—any feature you can least conveniently spare! See you those twin doorways? Tall and narrow they loom upon you—severely simple their outline—massive the masonry between—black as midnight the darkness within! Sir, of what do they mind you?

Ven. Of vaults, Sir, and of charnel-houses.

Lun. This is a goodly fancy, and yet they are not vaults. No, Sir, you see before you a Railway Tunnel!

Ven. ’Tis very strange!

Lun. But no less true than strange. Mark me. ’Tis love, ’tis love, that makes the world go round! Society goes round of itself. In circles. Military society in military circles. Circles must needs have centres. Military circles military centres.

Ven. Sir, I fail to see—

Lun. Lo you, said our Rulers, Oxford shall be a military centre! Then the chiefest of them (glad in countenance, yet stony, I wot, in heart) so ordered it by his underling (I remember me not his name, yet is he one that can play a card well, and so serveth meetly the behests of that mighty one, who played of late in Ireland a game of cribbage such as no man, who saw it, may lightly forget); and then. Sir, this great College, ever loyal and generous, gave this Quadrangle as a Railway Terminus, whereby the troops might come and go. By that Tunnel, Sir, the line will enter.

Pisc. But, Sir, I see no rails.

Lun. Patience, good Sir! For railing we look to the Public. The College doth but furnish sleepers.

Pisc. And the design of that Tunnel is—

Lun. Is mine, Sir! Oh, the fancy! Oh, the wit! Oh, the rich vein of humour! When came the idea? I’ the mirk midnight. Whence came the idea? From a cheese-scoop! How came the idea? In a wild dream. Hearken, and I will tell. Form square, and prepare to receive a canonry! All the evening long I had seen lobsters marching around the table in unbroken order. Something sputtered in the candle—something hopped among the teathings—something pulsated, with an ineffable yearning, beneath the enraptured hearthrug! My heart told me something was coming—and something came! A voice cried ‘Cheese-scoop!’ and the Great Thought of my life flashed upon me! Placing an ancient Stilton cheese, to represent this venerable Quadrangle, on the chimney-piece, I retired to the further end of the room, armed only with a cheese-scoop, and with a dauntless courage awaited the word of command. Charge, Cheesetaster, charge! On, Stilton, on! With a yell and a bound I crossed the room, and plunged my scoop into the very heart of the foe! Once more! Another yell—another bound—another cavity scooped out! The deed was done!

Ven. And yet, Sir, if a cheese-scoop were your guide, these cavities must needs be circular.

Lun. They were so at the first—but, like the fickle Moon, my guardian satellite, I change as I go on. Oh, the rapture, Sir, of that wild moment! And did I reveal the Mighty Secret! Never, never! Day by day, week by week, behind a wooden screen, I wrought out that vision of beauty. The world came and went, and knew not of it. Oh, the ecstasy, when yesterday the Screen was swept away, and the Vision was a Reality! I stood by Tom-Gate, in that triumphal hour, and watched the passers by. They stopped! They stared!! They started!!! A thrill of envy paled their cheeks! Hoarse inarticulate words of delirious rapture rose to their lips! What withheld me—what, I ask you candidly, withheld me from leaping upon them, holding them in a frantic clutch, and yelling in their ears ‘’Tis mine, ’tis mine!’

Pisc. Perchance, the thought that—

Lun. You are right, Sir. The thought that there is a lunatic asylum in the neighbourhood, and that two medical certificates—but I will be calm. The deed is done. Let us change the subject. Even now a great musical performance is going on within. Wilt hear it? The Chapter give it—ha, ha! They give it!

Pisc. Sir, I will very gladly be their guest.

Lun. Then, guest, you have not guessed all! You shall be bled, Sir, ere you go! ’Tis love, ’tis love, that makes the hat go round! Stand and deliver! Vivat Regina! No money returned!

Pisc. How mean you, Sir?

Lun. I said, Sir, ‘No money returned!’

Pisc. And I said, Sir, ‘How mean—’

Lun. Sir, I am with you. You have heard of Bishops’ Charges? Sir, what are Bishops to Chapters? Oh, it goes to my heart to see these quaint devices! First, sixpence for use of a doorscraper. Then, fivepence for right of choosing by which archway to approach the door. Then, a poor threepence for turning of the handle. Then, a shilling a head for admission, and half-a-crown for every two-headed man. Now this, Sir, is manifestly unjust: for you are to note that the double of a shilling—

Pisc. I do surmise, Sir, that the case is rare.

Lun. And then, Sir, five shillings each for care of your umbrella! Hence comes it that each visitor of ready wit hides his umbrella, ere he enter, either by swallowing it (which is perilous to the health of the inner man), or by running it down within his coat, even from the nape of the neck, which indeed is the cause of that which you may have observed in me, namely, a certain stiffness in mine outward demeanour. Farewell, gentlemen, I go to hear the music. [Exit Lunatic.

Chapter III

A Conference of the Hunter with a Tutor, whilom the Angler his eyes be closed in sleep. The Angler awaking relateth his Vision, The Hunter chaunteth ‘A Bachanalian Ode’

PISCATOR, VENATOR, TUTOR.

Venator. He hath left us, but methinks we are not to lack company, for look you, another is even now at hand, gravely apparelled, and bearing upon his head Hoffmann’s Lexicon in four volumes folio.

Piscator. Trust me, this doth symbolise his craft. Good morrow. Sir. If I rightly interpret these that you bear with you, you are a teacher in this learned place?

Tutor. I am, Sir, a Tutor, and profess the teaching of divers unknown tongues.

Pisc. Sir, we are happy to have your company, and, if it trouble you not too much, we would gladly ask (as indeed we did ask another of your learned body, but understood not his reply) the cause of these new things we see around us, which indeed are as strange as they are new, and as unsightly as they are strange.

Tutor. Sir, I will tell you with all my heart. You must know then (for herein lies the pith of the matter) that the motto of the Governing Body is this:—

‘Diruit, ædificat, mutat quadrata rotundis;’ which I thus briefly expound.

Diruit. ‘It teareth down.’ Witness that fair opening which, like a glade in an ancient forest, we have made in the parapet at the sinistral extremity of the Hall. Even as a tree is the more admirable when the hewer’s axe hath all but severed its trunk—or as a row of pearly teeth, enshrined in ruby lips, are yet the more lovely for the loss of one—so, believe me, this our fair Quadrangle is but enhanced by that which foolish men in mockery call ‘the Trench.’

Ædificat. ‘It buildeth up.’ Witness that beauteous Belfry which, in its ethereal grace, seems ready to soar away even as we gaze upon it! Even as a railway-porter moves with an unwonted majesty when bearing a portmanteau on his head—or as I myself (to speak modestly) gain a new beauty from these massive tomes—or as ocean charms us most when the rectangular bathing-machine breaks the monotony of its curving marge—so are we blessed by the presence of that which an envious world hath dubbed ‘the Tea-chest.’

Mutat quadrata rotundis. ‘It exchangeth square things for round.’ Witness that series of square-headed doors and windows, so beautifully broken in upon by that double archway! For indeed, though simple (‘simplex munditiis,’ as the poet saith) it is matchless in its beauty. Had those twin archways been greater, they would but have matched those at the corners of the Quadrangle—had they been less, they would but have copied, with an abject servility, the doorways around them. In such things, it is only a vulgar mind that thinks of a match. The subject is lowe. We seek the Unique, the Eccentric! We glory in this two-fold excavation, which scoffers speak of as ‘the Tunnel’

Ven. Come, Sir, let me ask you a pleasant question. Why doth the Governing Body chuse for motto so trite a saying? It is, if I remember me aright, an example of a rule in the Latin Grammar.

Tutor. Sir, if we are not grammatical, we are nothing!

Ven. But for the Belfry, Sir. Sure none can look on it without an inward shudder?

Tutor. I will not gainsay it. But you are to note that it is not permanent. This shall serve its time, and a fairer edifice shall succeed it.

Ven. In good sooth I hope it. Yet for the time being it doth not, in that it is not permanent, the less disgrace the place. Drunkenness, Sir, is not permanent, and yet is held in no good esteem.

Tutor. ’Tis an apt simile.

Ven. And for these matchless arches (as you do most truly call them) would it not savour of more wholesome Art, had they matched the doorways, or the gateways?

Tutor. Sir, do you study the Mathematics?

Ven. I trust, Sir, I can do the Rule of Three as well as another: and for Long Division—

Tutor. You must know, then, that there be three Means treated of in Mathematics. For there is the Arithmetic Mean, the Geometric, and the Harmonic. And note further, that a Mean is that which falleth between two magnitudes. Thus it is, that the entrance you here behold falleth between the magnitudes of the doorways and the gateways, and is in truth the Non-harmonic Mean, the Mean Absolute. But that the Mean, or Middle, is ever the safer course, we have a notable ensample in Egyptian history, in which land (as travellers tell us) the Ibis standeth ever in the midst of the river Nile, so best to avoid the onslaught of the ravenous alligators, which infest the banks on either side: from which habit of that wise bird is derived the ancient maxim ‘Medio tutissimus Ibis.’

Ven. But wherefore be they two? Surely one arch were at once more comely and more convenient?

Tutor. Sir, so long as public approval be won, what matter for the arch? But that they are two, take this as sufficient explication —that they are too tall for doorways, too narrow for gateways; too light without, too dark within; too plain to be ornamental, and withal too fantastic to be useful. And if this be not enough, you are to note further that, were it all one arch, it must needs cut short one of those shafts which grace the Quadrangle on all sides—and that were a monstrous and unheard-of thing, in good sooth, look you.

Ven. In good sooth. Sir, if I look, I cannot miss seeing that there be three such shafts already cut short by doorways: so that it hath fair ensample to follow.

Tutor. Then will I take other ground, Sir, and affirm (for I trust I have not learned Logic in vain) that to cut short the shaft were a common and vulgar thing to do. But indeed a single arch, where folk might smoothly enter in, were wholly adverse to Nature, who formeth never a mouth without setting a tongue as an obstacle in the midst thereof.

Ven. Sir, do you tell me that the block of masonry, between the gateways, was left there of set purpose, to hinder those that would enter in?

Tutor. Trust me, it was even so; for firstly, we may thereby more easily controul the entering crowds (‘divide et impera’ say the Ancients), and secondly, in this matter a wise man will ever follow Nature. Thus, in the centre of a hall-door we usually place an umbrella-stand—in the midst of a wicket-gate, a milestone—what place so suited for a watchbox as the centre of a narrow bridge?—Yea, and in the most crowded thoroughfare, where the living tide flows thickest, there, in the midst of all, the true ideal architect doth ever plant an obelisk! You may have observed this?

Ven. (much bewildered). I may have done so, worthy Sir: and yet, methinks—

Tutor. I must now bid you farewell; for the music, which I would fain hear, is even now beginning.

Ven. Trust me, Sir, your discourse hath interested me hugely.

Tutor. Yet it hath, I fear me, somewhat wearied your friend, who is, as I perceive, in a deep slumber.

Ven. I had partly guessed it, by his loud and continuous snoring.

Tutor. You had best let him sleep on. He hath, I take it, a dull fancy, that cannot grasp the Great and the Sublime. And so farewell: I am bound for the music. [Exit Tutor.

Ven. I give you good day, good Sir. Awake, my Master! For the day weareth on, and we have catched no fish.

Pisc. Think not of fish, dear Scholar, but hearken! Trust me, I have seen such things in my dreams, as words may hardly compass! Come, Sir, sit down, and I’ll unfold to you, in such poor language as may best suit both my capacity and the briefness of our time.

The Vision of the Three T’s.

Methought that, in some byegone Age, I stood beside the waters of Mercury, and saw, reflected on its placid face, the grand old buildings of the Great Quadrangle: near me stood one of portly form and courtly mien, with scarlet gown, and broad-brimmed hat whose strings, wide-fluttering in the breezeless air, at once defied the laws of gravity and marked the reverend Cardinal! ’Twas Wolseys self! I would have spoken, but he raised his hand and pointed to the cloudless sky, from whence deep-muttering thunders now began to roll. I listened in wild terror.

Darkness gathered overhead, and through the gloom sobbingly down-floated a gigantic Box! With a fearful crash it settled upon the ancient College, which groaned beneath it, while a mocking voice cried ‘Ha! Hal’ I looked for Wolsey: he was gone. Down in those glassy depths lay the stalwart form, with scarlet mantle grandly wrapped around it: the broad-brimmed hat floated, boatlike, on the lake, while the strings with their complex tassels, still defying the laws of gravity, quivered in the air, and seemed to point a hundred fingers at the horrid Belfry! Around, on every side, spirits howled in the howling blast, blatant, stridulous!

A darker vision yet! A black gash appeared in the shuddering parapet! Spirits flitted hither and thither with averted face, and warning finger pressed to quivering lips!

Then a wild shriek rang through the air, as, with volcanic roar, two murky chasms burst upon the view, and the ancient College reeled giddily around me!

Spirits in patent-leather boots stole by on tiptoe, with hushed breath and eyes of ghastly terror! Spirits with cheap umbrellas, and unnecessary goloshes, hovered over me, sublimely pendant! Spirits with carpet-bags, dressed in complete suits of dittos, sped by me, shrieking ‘Away! Away! To the arrowy Rhine! To the rushing Guadalquiver! To Bath! To Jericho! To anywhere!’

Stand here with me and gaze. From this thrice-favoured spot, in one rapturous glance gather in, and brand for ever on the tablets of memory, the Vision of the Three T’s! To your left frowns the abysmal blackness of the tenebrous Tunnel. To your right yawns the terrible Trench. While far above, away from the sordid aims of Earth and the petty criticisms of Art, soars, tetragonal and tremendous, the tintinabulatory Tea-chest! Scholar, the Vision is complete!

Ven. I am glad on’t: for in good sooth I am a-hungered. How say you, my Master? Shall we not leave fishing, and fall to eating presently? And look you, here is a song, which I have chanced on in this book of ballads, and which methinks suits well the present time and this most ancient place.

Pisc. Nay then, let’s sit down. We shall I warrant you, make a good honest wholesome hungry nuncheon with a piece of powdered beef and a radish or two that I have in my fish-bag. And you shall sing us this same song as we eat.

Ven. Well then, I will sing: and I trust it may content you as well as your excellent discourse hath oft profited me.

[Venator chaunteth

A Bachanalian Ode.

Here’s to the Freshman of bashful eighteen!

Here’s to the Senior of twenty!

Here’s to the youth whose moustache can’t be seen!

And here’s to the man who has plenty!

Let the men Pass!

Out of the mass

I’ll warrant we’ll find you some fit for a Class!

Here’s to the Censors, who symbolise Sense,

Just as Mitres incorporate Might, Sir!

To the Bursar, who never expands the expense!

And the Readers, who always do right, Sir!

Tutor and Don,

Let them jog on!

I warrant they’ll rival the centuries gone!

Here’s to the Chapter, melodious crew!

Whose harmony surely intends well:

For, though it commences with ‘harm,’ it is true,

Yet its motto is ‘All’s well that ends well’!

’Tis love, I’ll be bound.

That makes it go round!

For ‘In for a penny is in for a pound’!

Here’s to the Governing Body, whose Art

(For they’re Masters of Arts to a man. Sir!)

Seeks to beautify Christ Church in every part,

Though the method seems hardly to answer!

With three T’s it is graced—

Which letters are placed

To stand for the names of Tact, Talent, and Taste!

Pisc. I thank you, good Scholar, for this piece of merriment, and this Song, which was well humoured by the maker, and well rendered by you.

Ven. Oh me! Look you. Master! A fish, a fish!

Pisc. Then let us hook it.

[They hook it.